Wooden Funerary Models: a Snapshot in Time?

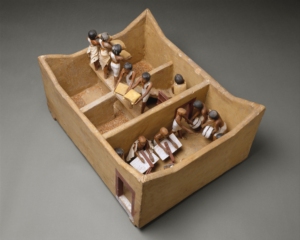

Paused mid-motion for millennia, five figures stand, about to pour grain from the second storey into three mostly empty storage areas; a sixth figure with a grain bag on his back perpetually makes his way towards the stairs, and yet more figures crouch, ready to account for grain brought through the single entryway into a granary from the tomb of Meketre, royal chief steward from the Middle Kingdom.

The granary, along with twenty-three other exceptionally well-preserved painted three-dimensional wooden scenes from Meketre’s tomb (now divided between the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation), are often regarded as exemplars par excellence of funerary models.

Figure 1: Model of a Granary with Scribes. Dynasty 12. Tomb of Meketre (TT 280), Southern Asasif, Thebes. Metropolitan Museum of Art 20.3.1 Source here.

What are Funerary Models?

Funerary or tomb models generally refer to three-dimensional painted wooden scenes in tombs and burial shafts across Egypt from the late Old Kingdom to the late Middle Kingdom (c.2246-1840 BCE). These models depicted scenes of agriculture, food and craft production, transport, and the bearing of offerings. From late Dynasty 4, limestone serving statues of a single figure milling grain, butchering animals, or playing the harp, among other activities, were placed in the serdabs, inaccessible statue chambers, of elite Old Kingdom tombs (Roth 2002).

During Pepi II’s reign (c.2246–2152 BCE), these figures fell out of use, and instead, these mostly wooden scenes with groups of figures undertaking similar activities – what we call funerary models – were placed in burial chambers, niches, pits outside tombs, floors of the entrances of tombs, burial shaft superstructures, or serdabs (Tooley 2001).

Figure 2: Statue of Nebetempet, daughter of Nikauinpu, grinding grain. Dynasty 5. Giza. Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, E10622. Courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago. Source here.

A typical Middle Kingdom elite burial would have models of craft or food production, offering bearers and boats. For example, the burial of physician Neferi from Banī Ḥasan in Middle Egypt had a granary, a baker, two offering bearers, a brewery, and two boats (Tooley 1989, 48). There were also exceptional burials: local governor Djehutynakht’s tomb, in the neighbouring cemetery, Dayr al-Barshā, contained 58 model boats and numerous other models, including offering bearers and scenes of craft or food production.

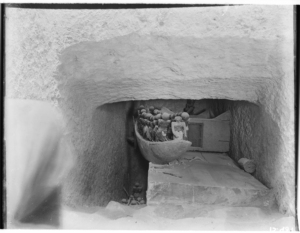

Figure 3: The Burial Shaft of Neferi. Dynasty 12. Tomb 116, Banī Ḥasan. Negative B-481. Image courtesy of the Garstang Museum of Archaeology, University of Liverpool

Funerary models ceased to appear in burials by the end of Senwosret III’s reign, except for a few model boats in Second Intermediate Period and New Kingdom funerary contexts, including the burials of Queen Ahhotep (c.1580-1525 BCE) and King Tutankhamun (c. 1336–1327 BCE).

Interpreting Funerary Models

On his discovery of the models in the Tomb of Meketre, American Egyptologist Herbert Winlock wrote: “I even suspect that some of [Meketre’s] grandchildren had sneaked in and played with them while they were at that house in ancient Thebes” (Winlock 1955, 8). Although this was not Winlock’s formal interpretation of the models, the idea that the models appear toy-like to a modern audience hints at their appeal. Such was the appeal that there was significant pressure from collectors and museums for complete models, resulting in modified or combined models and modern creations also entering collections worldwide.

Figure 4: Travelling Boat being Rowed. Dynasty 12. Tomb of Meketre (TT 280), Southern Asasif, Thebes. Metropolitan Museum of Art 20.3.1. Source here.

The activities depicted in the funerary models share many similarities with ancient tomb wall scenes. Traditionally, these models have been interpreted as a substitution or duplication of the tomb wall scenes, able to be enlivened in the afterlife to work on behalf of the deceased with whom they were interred. However, Georgia Barker has convincingly argued that a “funerary model was not simply a duplicate or substitute of the wall scene but formed a distinct type of artistic representation that was specifically conceived to provision the deceased for eternity” (Barker 2022, 192). The interaction between the living and tomb chapel wall scenes was key to them as a medium; they were there to encourage participation in the mortuary cult, whereas models were only accessible to the deceased, providing “a direct connection between the services offered by models and the tomb owner’s afterlife” (Barker 2022, 192).

Recent studies of ancient Egyptian funerary models have continued to challenge these traditional interpretations, proposing multiple ways of understanding their functions and purposes. Camilla Di Biase-Dyson proposed rethinking the term “model” as it does not fully encompass their function; she advocated viewing them as communicative tools, not simply representations of scenes. Taking a cognitive approach, Di Biase-Dyson asserted that models were not only “shaped by human ideas, but they shape those ideas in turn” (Di Biase-Dyson 2023, 12). Rune Nyord reasoned that rather than magical substitutes, these models represented and connected to activities in the mortuary cult and estates and the people performing them (Nyord 2020). Monika Zöller-Engelhardt argued that aesthetics was an aspect of a funerary model’s broader purposes within the burial assemblage, for which she proposed a range of possible purposes, including “magico-religious provisioning for the afterlife” and funerary ritual roles, among others, calling for us to consider “what an object does instead of what an object means” (Zöller-Engelhardt 2023, 633).

The idea of a model, like Meketre’s granary, as a snapshot, highlights the appeal to scholars and modern viewers alike in the potential of models to expand our understanding of ancient Egyptian daily life. Boat models, for example, have been examined to investigate ancient Egyptian boat building, crews, and navigation. However, as recent scholarship mentioned above has emphasised, this potential to offer insight into ancient Egyptian daily life must be held in the context of their intended function(s) and purpose(s) within ancient Egyptian funerary culture.

Bibliography and further reading

Barker, Georgia. 2022. Preparing for Eternity: Funerary Models and Wall Scenes from the Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdoms. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

Di Biase-Dyson, Camilla. 2023. “Building Ideas out of Wood. What Ancient Egyptian Funerary ‘Models’ Tell Us about Thought and Communication.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 33 (3): 413–29.

Eschenbrenner-Diemer, Gersande. 2023. “(Re)Connecting Artefacts and Thinking in the Afterlife: The Case of Wooden Funerary Models.” In Variability in the Earlier Egyptian Mortuary Texts, edited by Carlos Gracia Zamacona, 304–39. Leiden: Brill.

Nyord, Rune. 2020. “Servant Figurines from Egyptian Tombs: Whom Did They Depict, and How Did They Work?” Ancient Near East Today, 2020.

Powell, Sam, Georgia Barker, Monika Zöller-Engelhardt, Emily Whitehead, Rune Nyord, and Gersande Eschenbrenner-Diemer. 2024. “Model Behaviour Study Afternoon.” https://woodenfuneraryfigures.abasetcollections.com/Info/Details/55?f=Model_Behaviour_Study_Afternoon.

Roth, Ann Macy. 2002. “The Meaning of Menial Labor: ‘Servant Statues’ in Old Kingdom Serdabs.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 39:103.

Tooley, Angela M. J. 1989. “Middle Kingdom Burial Customs. A Study of Wooden Models and Related Material.” Ph.D., Liverpool: University of Liverpool.

———. 2001. “Models.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald B Redford. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Winlock, Herbert E. 1955. Models of Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: From the Tomb of Meket-Rēʻ at Thebes. Cambridge: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Harvard University Press.

Zöller-Engelhardt, Monika. 2023. “Aesthetics of Anthropomorphous Funerary Wooden Models: Case Studies from Asyut.” In Schöne Denkmäler Sind Entstanden. Studien Zu Ehren von Ursula Verhoeven, edited by Simone Gerhards et al., 621–36. Heidelberg: Propylaeum.