Tutankhamun's Sticks

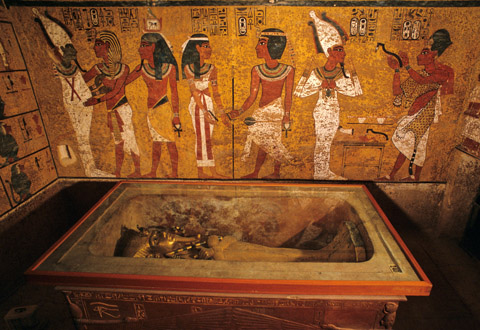

Tutankhamun remains one of ancient Egypt’s most iconic pharaohs. In terms of religious beliefs, social structures, material culture and burial rituals, the tomb of Tutankhamun provides Egyptologists with unprecedented knowledge and understanding of kings during the 18th dynasty. However, since the famous discovery of the tomb in 1922, much of the material remains understudied or unpublished. Among these materials is an assemblage of more than 130 sticks and staves. Scholars suggest Tutankhamun was buried with these items because he was disabled and needed walking aids. But other kings of the 18th dynasty used such sticks and staves. By comparing these material culture remains with the staves found from the tomb of Tutankhamun, my alternative view is that these items served as essential kingly insignia during his rule, not as walking aids.

The burial of Tutankhamun was not the first tomb from ancient Egypt containing a large number of staves. When discovered by Reisner in 1915, the tomb of Djehutynakht at Deir el Bersha featured more than 250 sticks and staves. Also discovered there were different types of insignia related to kingship, including maces and model was-scepters. Among the staff assemblage of Tutankhamun were was-scepters, abet-staves, crooks and others. Though such collections are not found in every burial, the size and variety in the tomb of Djehutynakht, compared to the staves buried with Tutankhamun, indicates it was not uncommon for ancient Egyptians to be buried with many different staves.

Other pharaohs of the 18th dynasty were buried with the same sticks and staves they were depicted using in life. Though fragmentary, evidence from the tombs of Amenhotep II, Thutmosis IV and Amenhotep III indicates the presence of staves. Unfortunately, the poor state of preservation and the small amount of material make it impossible to compare these items with Tutankhamun’s.

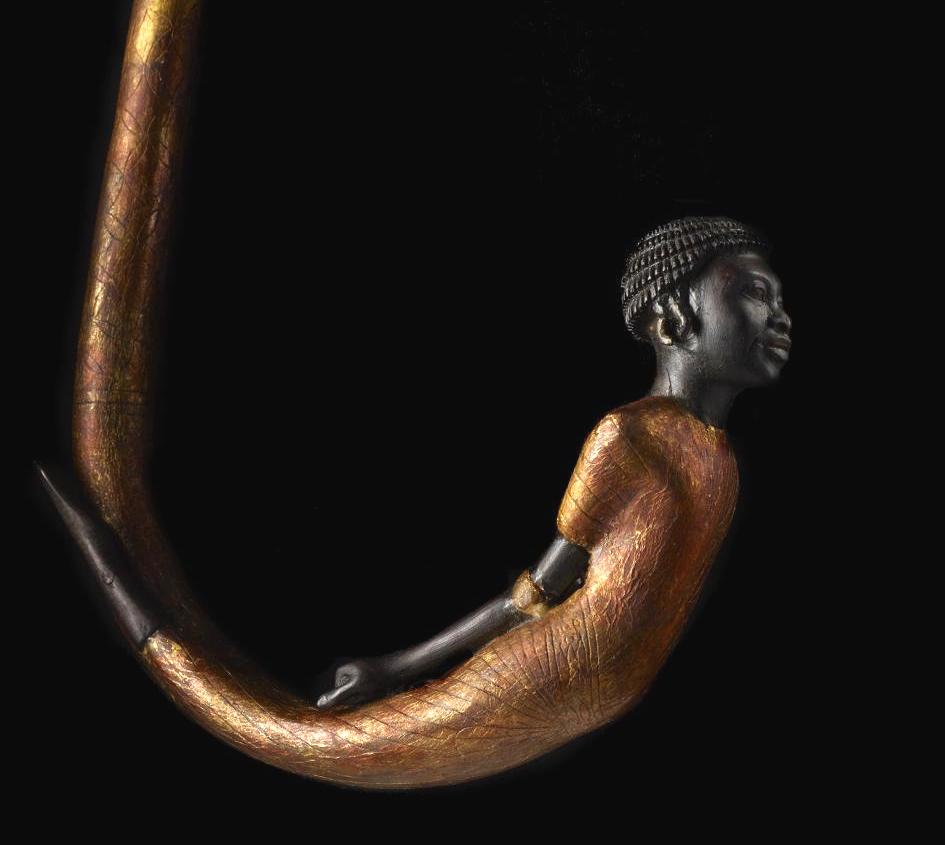

The sticks themselves are not the only evidence of royal staff use as there are many artistic depictions of kings using sticks. In the burial of Tutankhamun, several artifacts depict the young pharaoh carrying a stick or staff. Such depictions come from different statues and statuettes found within the Antechamber and the Treasury. Of all of Tutankhamun’s statues, the most notable are the two ka statues of the king (JE 60707 and JE 60708), found flanking the entrance to the burial chamber. Meanwhile, blocks from the memorial temple of Tutankhamun, which were recovered from Karnak, show a cult statue of the king carrying a staff and a mace. In both depictions, it appears the cult-image of Tutankhamun carries a long, straight staff. These and other depictions have parallels with earlier 18th-dynasty tombs in the Valley of the Kings, including Thutmosis III (CG 24901), Amenhotep II (CG 24598), and Thutmosis IV (CG 46047).

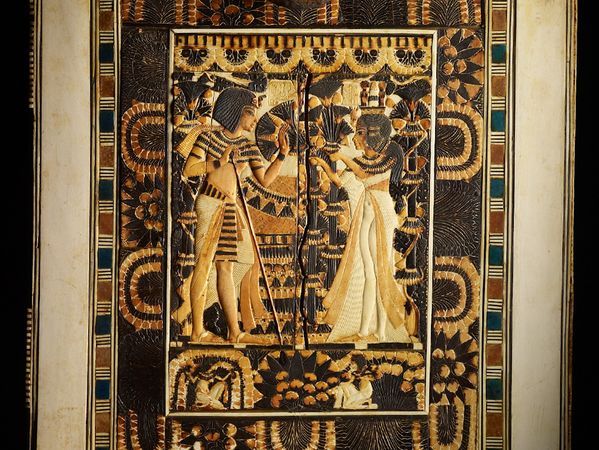

The king also holds a staff in a burial image on an ivory inlayed box found in the Annex (JE 61477). Assuming this box was originally inscribed for Tutankhamun, the scene depicts the pharaoh and his queen. Tutankhamun is leaning on a staff with his right hand, while his left hand reaches out for a bouquet of flowers that Ankhesenamun offers to him. Though it is tempting to conclude the young pharaoh is using the staff for support, the scene actually is a remnant of the Amarna-style art. Similar scenes are found in in two private Amarna tombs: The burial of Parennefer (Amarna Tomb 7), where the royal family makes a public appearance and Akhenaten holds a long staff in a similar manner, and the tomb of Meryra (Amarna Tomb 2), where the deceased tomb owner is shown receiving the Gold of Valor from Akhenaten, who leans on a straight staff. Other examples from the Amarna period depict private individuals holding staves in similar fashion. In the Memphite tomb of Iniuia, a near-identical scene to Tutankhamun’s shows the deceased leaning on a staff with his left hand, while his right hand reaches for a bouquet of flowers offered by his wife.

Other depictions from the 18th dynasty show kings using staves in different settings, most typically sitting in a kiosk and holding court. Another common depiction features 18th-dynasty kings with staves in tribute scenes – either during the New Years Festival or for Syrian and Nubian tributes. From the tomb of Amunedjeh (TT84), two Nubian tribute bearers bring a staff labeled as “tisu” to the king. This type of staff is listed among the New Years gifts in the tomb of Kenamun (TT93), where 30 such staves are presented to Amenhotep II. An inscription nearby states the tisu staves are made of ebony, decorated with a gold ferrule and silver butt. Such examples of the tisu staff were found in the annex of Tutankhamun – also made of ebony, decorated with a golden ferrule and an electrum butt. Perhaps then, some staves from the tomb of Tutankhamun may have been tribute gifts presented by foreign envoys or during a New Year’s festival.

Because the precise use and function of sticks and staves as kingly regalia is not fully understood, scholars will continue to reinterpret the staff assemblage of Tutankhamun’s tomb. One group, led by Drs. Salima Ikram and Andre Veldmeijer, founded the Tutankhamun Sticks and Staves Project to document the items in the assemblage, analyze the technologies used to produce them, identify their uses and understand their role and position in Tutankhamun’s tomb, death and life. Though some of these many items could have been walking aids, it is more likely Tutankhamun used these staves as royal regalia for religious rituals and public appearances.

Recommended Reading

Brown, Nicholas R. 2017. “Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: the Use of Staves for the Divine Transformation of the Deceased in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 53: 189-201.

Brown, Nicholas R. 2017. “Traversing into the Afterlife: Identifying a Wooden Fragment from the South Tombs Cemetery.” Horizon: the Amarna Project and Amarna Trust Newsletter, Issue 18, Autumn 2017: 12-13.

Fischer, H. G. 1978b. “Notes on Sticks and Staves.” MMJ 13, 5-32.

Gordon, A. H. and C. W. Schwabe 1995. “The Egyptian wAs-scepter and its modern analogues: uses as symbols of divine power or authority.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 32, 185-196.

Hassan, A. 1976. Stöcke und Stäbe im Pharaonischen Ägypten. Munich: Deutscher Kuntsverlag.

Jéquier, G. 1921. Les Frises d’Objets des Sarcophages du Moyen-Empire. Cairo: IFAO.

Mace, A. C., & H. E. Winlock. 1916. The Tomb of Senebtisi at Lisht. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Press.