Stelae: Ancient Egypt's Versatile Monumental Form

A stela is an upright monument containing information in the form of texts, images or a combination of the two. Stelae have been used to commemorate people or events, to delineate physical spaces or as objects through which to access the dead or divine. Such monuments were made by a variety of cultures in the ancient world, including the Assyrians, Maya, Greeks and Romans. The most common Egyptian term for a stela is wedj, which originally meant “command” and stems from wedj–nesu, “royal decree.” Various qualifiers could be used to further classify wedj, such as wedj-her-tash – “boundary stela” – or wedj-en-nekhtu – “victory stela.” Several other terms, including ahau (from aha, “to stand”), were also used to describe this type of monument.

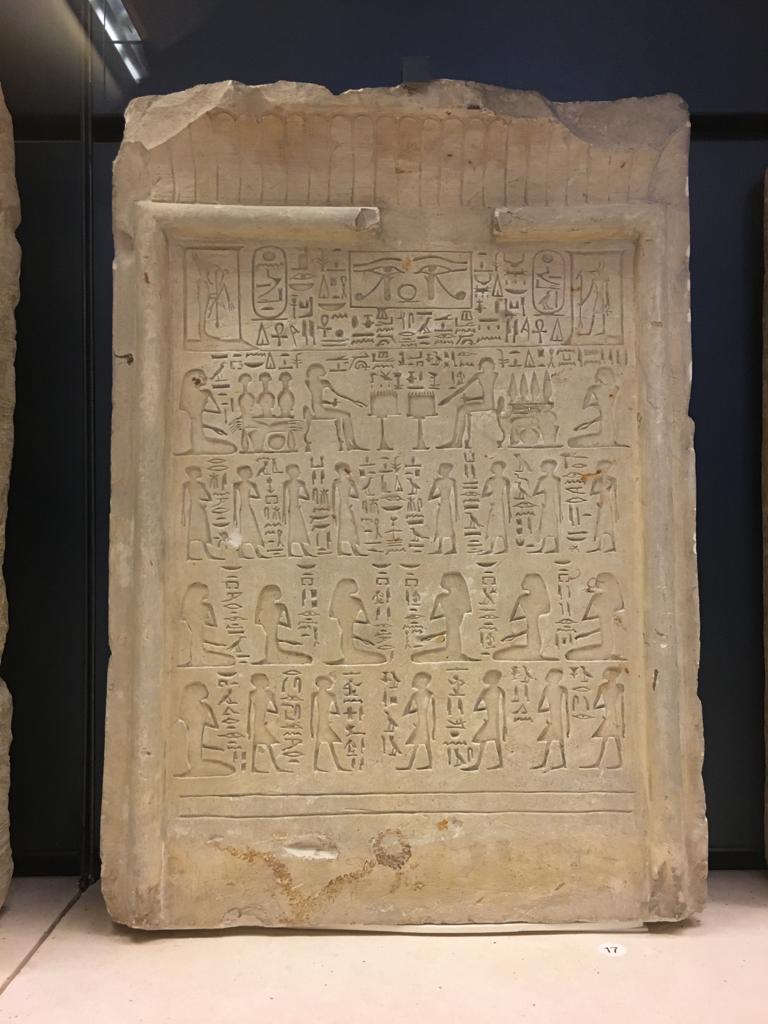

Egyptian stelae originated during the first dynasty as burial markers in the necropolis at Abydos, in the form of round-topped stone pillars inscribed with the king’s name and stone slabs with the names and titles of his officials. Later examples were either freestanding, set into the walls of architectural features or carved into rock outcrops. They are usually round-topped or rectangular in shape, made either from stone or painted wood, and range in size from only a few centimeters to more than 25 feet high. Many have dedicated images, epithets or figural scenes set apart from the text, such as in the curved upper portion of a round-topped stela. This area, called the lunette, was first delineated from the rest of the stela during the reign of Pepi I, and from the reign of Senwosret III, its contents began to be divided vertically into axisymmetric halves. The upper portions of stelae often contain images that speak to the divine support and protection of their contents, such as representations of the sky, the winged sun disk, shen-rings and wedjat-eyes.

Stelae were commissioned by both royal and non-royal patrons and fulfilled a number of functions in Egyptian society. Inside or on the façades of tombs, funerary stelae recorded the names, titles and representations of the deceased to keep their memories alive. Such stelae often depict the tomb owner (with or without their family) before an offering table or heap of goods, imploring living visitors to donate to the cause or to give a “voice offering” in lieu of physical food and drink. False-door stelae, which appeared at the start of the Old Kingdom, served as an entryway into the tomb chapel through which the deceased could access the bread, beer and other goods that had been left to sustain them. Good evidence from the Middle Kingdom onward supports the existence of workshops to produce private stelae.

Stelae also served as stand-ins for those who wanted to be “present” at Abydos – the mythical burial place of Osiris – but whose tombs were located elsewhere. One famous example of this type is that of the 12th-dynasty treasurer, Ikhernofret, describing the so-called mysteries of Osiris. Votive stelae, another type, were erected in or near temples or in the home, in exchange for healing or the fulfillment of wishes. From the Ramesside period onward, some bear images of ears so the patron’s plea was more likely to be heard by the god they invoked. “Magical” stelae, or cippi, originating in the Late period, were inscribed with spells and images of the child Horus in mastery of dangerous animals; water poured over these stelae was thought to absorb the essence of their contents and could be sipped as a remedy for stings or bites.

The royal establishment erected commemorative stelae in temples on the occasion of a notable event or accomplishment. Victory stelae similarly memorialized and publicized Egyptian military campaigns and were set up along the routes of those expeditions; they usually contain images of the king smiting his enemies – at once celebratory, cautionary and protective. Quarrying and mining expeditions were also commemorated with stelae, such as in the Wadi Hammamat, where their texts report the miracles that occurred there during the reign of Mentuhotep IV and the names of the men who witnessed them. Stelae were also used to record the opening of new quarries.

Ordinances and decrees were also recorded on stelae. Such texts would have been written on papyrus and deposited in archives; copying one on a stela implies a desire for greater permanence and visibility, although probably not full comprehension, as most Egyptians could not read. Examples of such texts include the Decree of Nectanebo I, inscribed on twin stelae erected at Naukratis and Thonis-Heracleion, which earmarks a portion of taxable goods for the temple of Neith, and the Nauri Decree of Seti I, which regulates the transport of goods from Nubia to the temple at Abydos from a tall hill facing the direction of river traffic back to Egypt.

Boundary stelae – yet another type – marked the edges of fields, estates and districts, with the size and location of the territory they enclosed indicated in their texts. Such monuments were also used to mark the edges of cities – the boundary stelae for the Amarna-period capital, Akhetaten, were carved into the surrounding cliffs – and of Egypt’s empire in Nubia and the Levant. The Middle Kingdom imperial boundary stelae at Semna and Uronarti in Nubia were probably set into the mudbrick walls of fortresses; their texts outlined the border-control policies of the time and stipulated that a king’s duty was to uphold the boundary of his father.

Each of the above functions was dictated by the texts and images a stela contained and the context in which it was erected and used. This was a truly versatile monumental form, employed over the whole of the pharaonic era through to the Coptic period.