The Search for Imhotep: Tomb of Architect-Turned-God Remains a Mystery

Of the many secrets of ancient Egypt’s pyramid builders, among the most intriguing is the undiscovered final resting place of one of the most famous Egyptian sages and scientists: Imhotep. Since Egyptology began as a scientific discipline in the 19th century, several generations of explorers and scientists have failed to identify where this esteemed, innovative figure in Old Kingdom history is buried. His tomb is important because it could reveal more about this important figure’s life and career. But that precise location remains a mystery despite most experts agreeing the tomb should be somewhere at today’s Saqqara and Abusir.

According to later legends, Imhotep – “he who comes in peace” – invented building in stone around 2600 BCE, at the beginning of the 3rd dynasty. This achievement corresponds with the spread of monumental stone architecture during the reign of Khasekhemwy, last king of the second dynasty and Djoser’s predecessor on the throne – and probably his father. While no break in political development seemed evident between the second and third dynasties, the reign of Djoser marked a new era characterized by an incredible rise in complexity of the Old Kingdom state. The first decorated tombs in Abusir and the Saqqara necropolis date to Djoser’s reign, and he was the first king to send mining expeditions to Sinai to produce copper. Also from his reign came the first fully-developed grammatical sentences known in ancient Egyptian. The first vizier recorded by name – Kaimen – is attested as a donor of several stone vessels to the king’s cult. Djoser also erected a small temple in Heliopolis, later a famous cult place of the sun god, Ra. There is every reason to believe that Imhotep played a major role in at least some of these royal accomplishments.

Of course, Imhotep is most famous as the builder of Djoser’s unprecedented step pyramid complex, called the “The Refreshment of the Gods.” Imhotep designed this complex on a scale that surpassed everything achieved by his predecessors. The pyramid complex was surrounded by a monumental trench 40 meters (over 130 feet) wide. Inside a 750 by 600-meter perimeter, the huge burial precinct was enclosed with a stone wall of 10.5 meters (nearly 35 feet). Imhotep replaced the traditional organic and mudbrick building materials with small blocks of limestone. Because he lacked experience with this innovative material, he used stone blocks close to the same size as the traditional mudbricks. But the stone allowed Imhotep to work toward his goal of designing a true copy of the king’s earthly palace as an “eternal” residence in stone. In this complex, after his death and interment, Djoser was to become an immortal god and, during religious feasts, meet with other gods and goddesses of the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Imhotep placed the actual final resting place for the king more than 20 meters (65 feet) below the six-stepped pyramid. Even today, despite decades spent exploring the complex by different scientific methods and equipment, large areas to the north and west of the pyramid remain unexcavated and probably hide major secrets of Djoser and his famous architect.

Imhotep’s extraordinary position in Egyptian society is documented on the statue base of Djoser – now kept in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. That base contains the most important and only known titles of Imhotep: “prince, royal seal-bearer of the king of Lower Egypt, high priest of Heliopolis, director of sculptors.” Given the extraordinary privilege of being named on a royal statue, it is supposed that Imhotep was, in fact, considered a respected member of the king’s family.

He undoubtedly survived King Djoser, as Imhotep’s name also occurs in the next royal complex – that of King Sekhemkhet in Saqqara. Imhotep probably died during the reign of the last king of the third dynasty, Huni. Thus we can estimate that Imhotep lived for most of the 26th century BCE.

But the architect’s fame only grew. During the New Kingdom, Imhotep was venerated and became the patron of scribes. He was also considered to be the son of Ptah, the principal deity of ancient Memphis, and a woman named Khereduankh. His cult peaked during the Late period when he was deified and gained his own cult, temples and priesthood – first on a local level in Saqqara. This development probably relates to when the Egyptian elite, after being exposed to different cultural, intellectual, political and military pressures from abroad, looked toward their remote past to establish a renaissance of their own culture. Imhotep’s cult continued to expand until the last period of native rule in Egypt, when he assumed the status of a god for his mastery in healing. The Greeks even identified him with their own god of medicine, Asclepius.

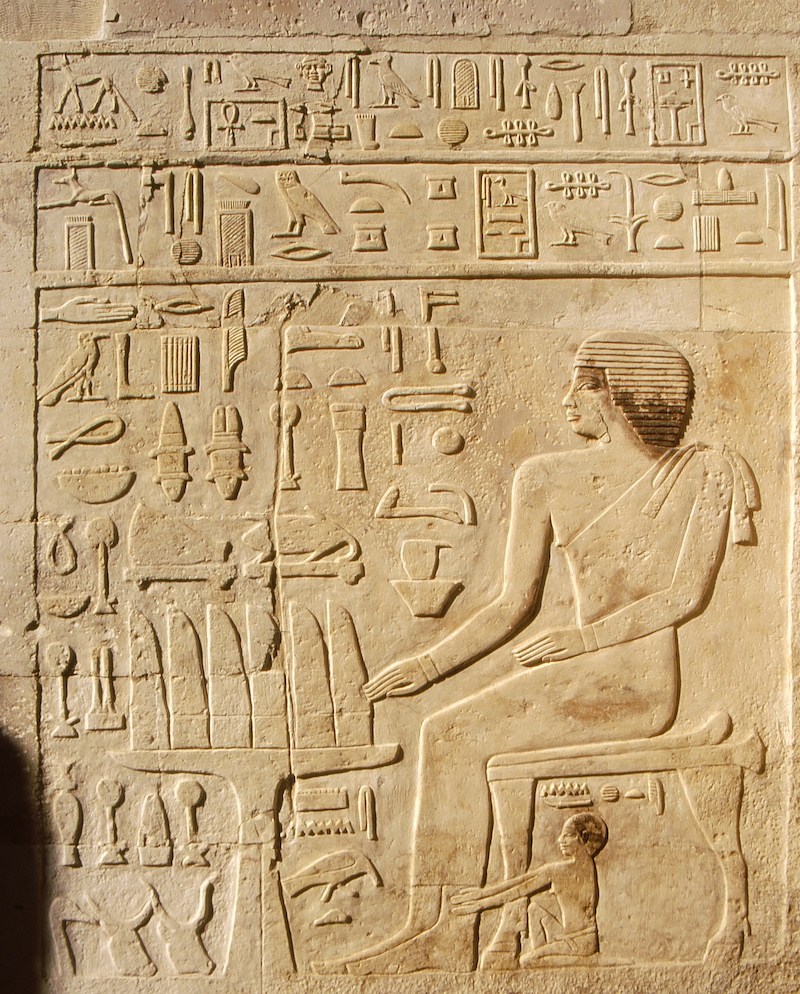

During these periods, Imhotep was represented by many statues and bronze statuettes dated to the New Kingdom and the first millennium BCE They portray him as a seated wise man, head covered with a cape, studying an unrolled papyrus on his knees. Imhotep’s vision, wisdom and authority are also described in a rock-cut inscription dated to the 18th year of Ptolemaios V from the 3rd century BCE. The inscription is antedated to the reign of Djoser, when he was dealing with a drought of seven years. In the inscription, Djoser asks Imhotep to save the country, a task that Imhotep fullfils. Imhotep’s popularity also is attested by a small temple in Philae at Aswan dated to the reign of Ptolemaios V. The architect’s cult survived till Graeco-Roman times.

Yet, despite the efforts of archaeologists over many decades, Imhotep’s tomb has never been found. Scholars have two theories: His tomb could be somewhere in Djoser’s burial complex because he was member of the royal family. Or Imhotep’s tomb may lay somewhere in North Saqqara, where most well-known tombs of the period are located. British archaeologist W.B. Emery searched at North Saqqara and believed the tomb labeled S 3518 to be Imhotep’s final place of rest. Emery’s reasoning was based on that tomb’s elaborate system of cult rooms, votive offerings and seal imprints with Djoser’s name. But experts also agree the famous mystery tomb could already have been found elsewhere – but never identified because of deterioration and a lack of surviving evidence. If you ask me, though, I am convinced that the tomb of Imhotep has yet to be discovered.

Recommended Reading

Bárta, M. 2011. Journey to the West. The world of the Old Kingdom tombs in ancient Egypt, Charles University, Prague.

Lehner, M. 2008. The complete pyramids. Thames & Hudson, London.

Wildung, D., 1977. Egyptian Saints. Deification in Pharaonic Egypt. New York.