The Rise of the Ramessides: How a Military Family from the Nile Delta Founded One of Egypt’s Most Celebrated Dynasties

When studying or reading about ancient Egypt, it is difficult to avoid mentions of Ramses II. The third ruler of the 19th dynasty looms large in the records of Egyptian history partially because of his uncommonly long reign and the resultant large-scale building projects this longevity allowed. While Ramses was no doubt an able king, and certainly one who left his mark, he was not the only significant ruler of his dynasty. The Ramesside period (usually given as the 19th and 20th dynasties, ending with Ramses XI toward the end of the second millennium BCE) represents a high-point of Egyptian construction, foreign policy and material culture.

The rise of the Ramesside dynasty owes a great deal to a combination of societal developments and political choices going back to the height of the 18th dynasty. As that era’s rulers, such as Amenhotep II and Thutmosis III, expanded Egypt’s sphere-of-interest through large-scale military campaigns in Nubia and Western Asia, the nature of the Egyptian elite began to change. Several families and individuals became powerful and prominent because of their involvement in the military. This increased militarization of the elite culminated in the rise of Horemheb to the throne of Egypt by what may have been a military coup.

As a leader, Horemheb was in many ways a mixture of the old and the new. He was a product of the 18th dynasty, closely aligned during his early, non-royal career with the post-Amarna Period rulers. Simultaneously, he was a military man from a somewhat unknown family in Northern Egypt. Later in his reign, it became clear that he would not be able to establish his own bloodline. Probably fearing a continuation of the succession chaos that occurred after the death of Akhenaten, Horemheb looked to his allies to ensure his legacy. His eyes fell on Paramessu, a fortress commander who served as one of his two viziers. Paramessu, like Horemheb, came from a northern family and was not part of the Theban elite. The vizier’s family seems to have had connections to the eastern Nile Delta and, in particular, the region around the old Hyksos capital of Avaris. More importantly, Paramessu already had a son: Seti.

In naming Paramessu as his successor, Horemheb secured a succession not just after his death, but also following the death of Paramessu himself. It is possible that Horemheb lived to see Seti have a son – the future Ramses II – further cementing the ascendant Ramesside dynasty. When Horemheb died, Paramessu succeeded him, taking the nomen ‘Re has birthed him’, Ra-mes-su, anglicized as Ramses I. Ramses however, did not rule long. He died most likely after less than two years, leaving his relatively young son to rule as Seti I.

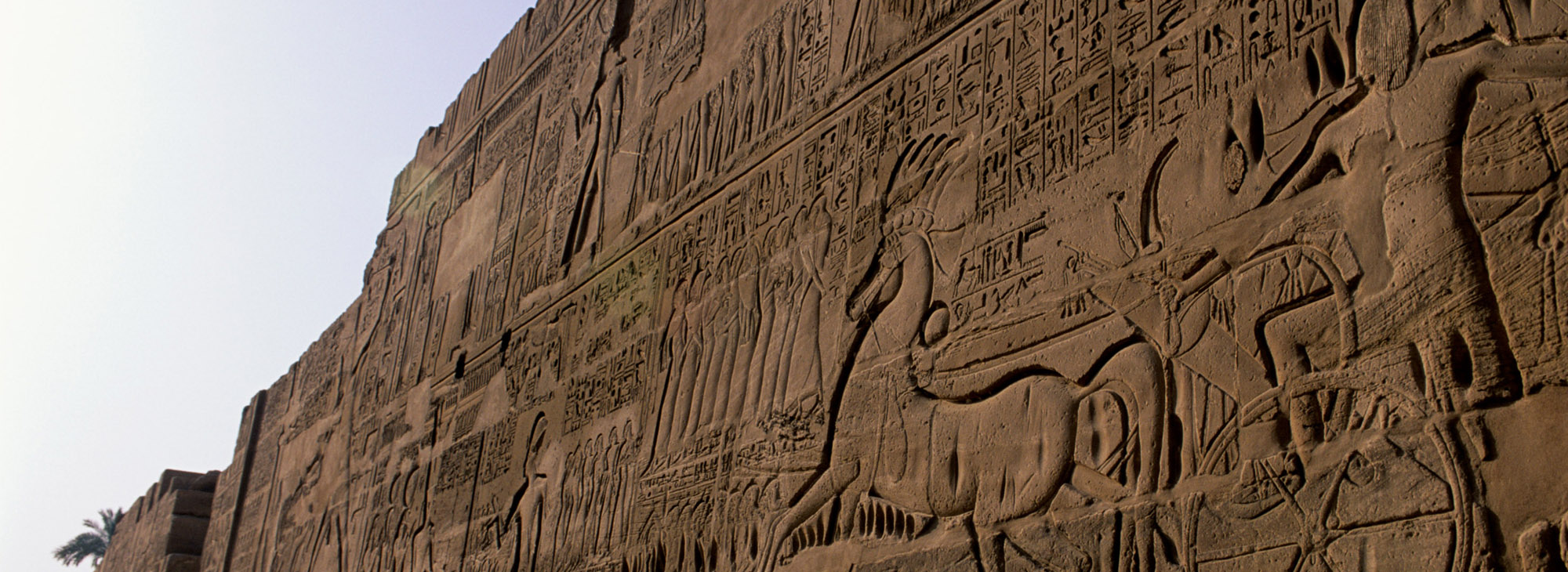

The precise origins of Ramses I are difficult to discern. Most of the information about his family comes from the 400-Year Stela, an inscription at the Temple of Seth in Avaris during the reign of Ramses II. This inscription provides several titles held by Seti I during the reign of Horemheb and also lists Ramses I as Horemheb’s ‘Deputy in Upper and Lower Egypt.’ But researchers cannot rely entirely on the 400-Year Stela for its inherently political purpose: It was carved during the reign of Ramses II to legitimize his reign, so its inscription likely has a political agenda. Furthermore, the stela itself is damaged and the entire text has not been preserved.

Other textual sources about the early history of the Ramesside dynasty are equally vague and troublesome. A fragment of a votive stela currently held in the collection of the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago (OI 11456) is dedicated to a troop-commander by the name of Seti. Appearing alongside Seti are his son, Paramessu, and his brother Khaemwaset. While it is not certain, this Paramessu may in fact be Ramses I in the early stages of his career. That would make his father, the troop-commander Seti, the great-grandfather of Ramses II and the earliest named member of the Ramesside dynasty in the historical record. A statue of this leader, alongside his son Paramessu, was also found at Karnak Temple, where in addition to ‘troop-commander’ he is given the title ‘judge.’

A final tantalizing piece of evidence for the origins of the Ramesside dynasty is found in diplomatic correspondence known collectively as the Amarna Letters. In two of the letters, EA234 and EA288, both written during the reigns of Akhenaten, an Egyptian commissioner (rabisu) named Sjuta figures prominently. Some scholars have speculated that this name may be an attempted literal rendering of the Egyptian name Sjuty, or – in the anglicized form – Seti. This commissioner could thus be the same troop-commander who appears on OI 11456 – the father of Ramses I and the grandfather of Seti I.

The Ramesside dynasty represented a clear departure from the Theban royal family of the 18th dynasty. The dynasty rose when Egypt’s standing in the world had been weakened, as had the country’s internal cohesion. Ramses I, Seti I, Ramses II and their immediate successors acted to reverse this trend, ruling within an existing international order in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, by the end of their dynasty, this very order would collapse and herald the end of the Egyptian New Kingdom, the established order of Great Kings and eventually the Mediterranean Bronze Age.