Imhotep: A Sage between Fiction and Reality

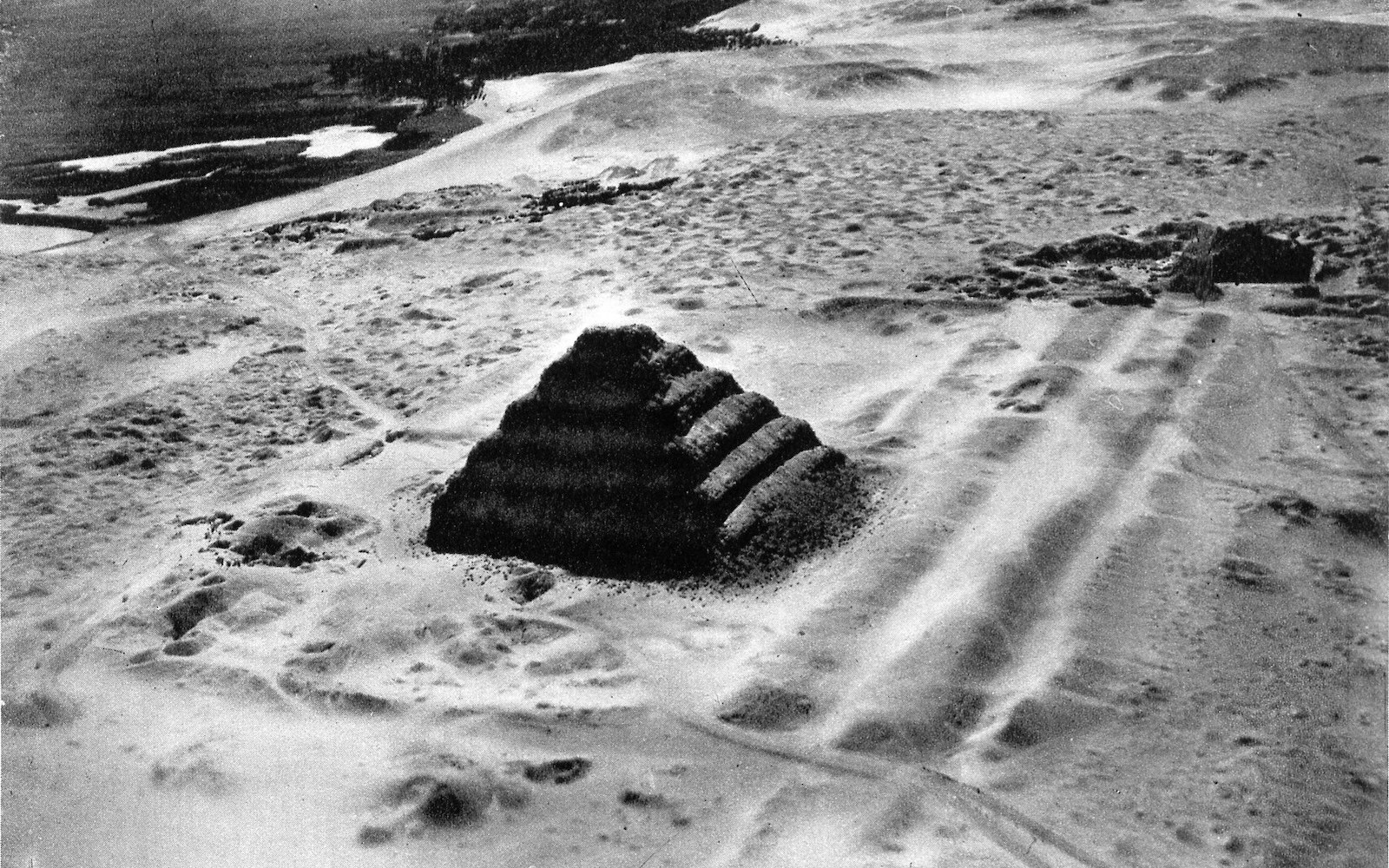

The name of Imhotep is associated in Egyptological literature with the first pyramid, the famed stepped tomb of king Netjerkhet, later known as Djoser “the holy one.” Knowledge of both historical figures is shrouded in legend because only a few sources from their time have been found. In the case of Imhotep, contemporary references are limited to two inscriptions mentioning his name and titles in connection with Djoser and his successor Sekhemkhet, both of the 3rd dynasty in the Old Kingdom (2686–2613 BCE). These titles call Imhotep the royal seal bearer and great of seers (priest of the temple of Heliopolis), as well as overseer of sculptors. There is no explicit mention of his role as architect of Djoser’s pyramid complex. Nevertheless, the presence of his name and titles on the base of a statue of this king is evidence of his elevated position in the royal court. The original location of this statue in the funerary complex of the king, plus the titles related to building and sculpture, point to a historic role as designer of Egypt’s first monumental structure in stone.

Despite the scarcity of actual information about his life, Imhotep’s achievements left such an impression that his memory not only survived but became a legend in the millennia following his death. By the New Kingdom he was listed as among the wise men of the past, also noted as the most ancient of them. In other sources, Imhotep is mentioned with sages such as Hordedef, Khakheperraseneb and Ptahhotep. Compositions attributed to all these authors have survived, supporting the inference that similar texts written by Imhotep may have circulated in the Middle and New Kingdoms. In fact, Manetho reports in his Aegyptiaka that Imhotep busied himself with writing. By the New Kingdom he was venerated as patron of scribes, but Imhotep’s image was elevated even more in the Late Period, when he started to be worshipped in the Memphis region and was considered to be son of the god Ptah. Imhotep’s cult image appears at this point: a seated figure wearing a cap and holding an unrolled papyrus on his lap. Several hundred bronze figurines depicting Imhotep in this guise have been found from this period.

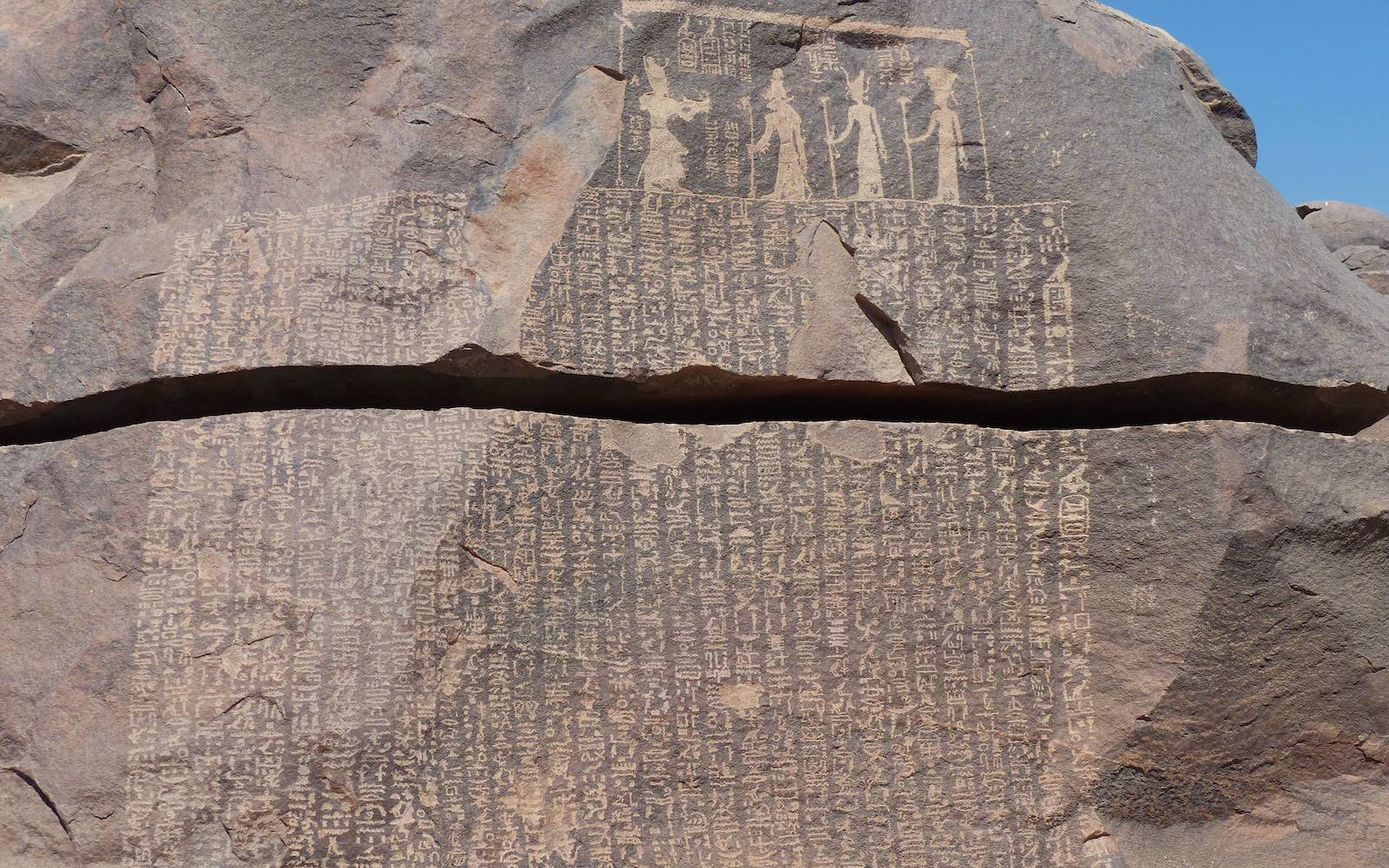

By the Late and Graeco-Roman periods, several narrative traditions were composed around Imhotep and Djoser. One papyrus from the Tebtunis Temple Library dating to the Roman period (P. Carlsberg 85) narrates different episodes of a fictionalized life of Imhotep. This text and other sources describe his divine father Ptah, his mother Khereduankh, and his sister Renpetneferet, sometimes also referred to as his wife. Imhotep is depicted as a powerful magician in Djoser’s royal court. In one episode, he travels to Assyria to recover the 42 limbs of Osiris and fights in a magical contest against an Assyrian sorceress. Another fragmentary episode refers to the “house of rest of pharaoh,” which might be a reference to Djoser’s Step Pyramid and to Imhotep’s involvement in its construction. Another text, the so-called Famine Stela, is set in the time of Djoser and Imhotep, although it was actually composed in the Ptolemaic period. The stela presents the monarch as a wise ruler worried about his starving country because of faulty Nile inundations over seven years. To solve the problem, Djoser consults Imhotep, who is described as a lector priest, son of the god Ptah, and “a member of the staff of the ibis”– connecting him with the cult of Thoth. Manetho may have consulted these narratives for his Aigyptiaka. In the sections of the Aigyptiaka concerning the reign of Djoser, Imhotep is described as devoted to medicine, as writing books and as the inventor of building with stone.

The attribution as healing god connected Imhotep with Asklepios, the Greek god of medicine. In a Greek horoscope (preserved in P. Louvre 2342bis), we find Imhotep in a list of wise men as “Asklepios, that is Imouthes, son of Hephaistos (i.e. Ptah).” In this list he is paired with Hermes, who was identified with the Egyptian Thoth, god of wisdom and writing. This association between Imhotep and Thoth also appears in a Demotic treatise for the initiation in the scribal profession, known in Egyptological literature as the Book of Thoth. A hymn honoring Imhotep is included in this treatise. The connection between Imhotep and Thoth, the latter as the Graeco-Egyptian Hermes Trismegistos, continued in the Greek Hermetica. During the Graeco-Roman period Imhotep was also associated with astronomy/astrology and with divination, appearing in this period as the author of astrological treatises. One unpublished astrological treatise opens with a frame narrative in which the actual treatise is described as having been composed by Imhotep, son of Ptah. The cult of Imhotep seems to have ended around the 4th century CE, but it survived in a transformed way. This occurred through the association of some of his cult places with the Biblical/Qur’anic prophet Joseph, whose narrative shared features with Imhotep’s Graeco-Roman fictionalized life, including the seven years of hunger and his role in divination.

Recommended Reading

Ryholt, K. “The Life of Imhotep (P. Carlsberg 85)” In G. Widmer and D. Devauchelle, Actes du IXe Congrès international des études démotiques: Paris, 31 août-3 septembre 2005. Cairo: Institut franc̜ais d’archéologie orientale, 2009. pp. 305–315.

Wildung, Deutscher. Imhotep und Amenhotep: Gottwerdung im alten Ägypten. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1977.