Facing Tutankhamun

Reprint from ARCE Bulletin number 188, Fall 2005 and page number 3-5

Usually, when I know that I will be opening a sealed tomb or having an archaeological adventure, I feel only excitement about the moment to come. But January 4th of 2005 was different. The next day, I was scheduled to enter KV62 in the Valley of the Kings and come face to face with Tutankhamun, an opportunity that I would normally have looked forward to with great anticipation. We planned to CT scan the mummy of the golden boy, and hoped to learn more about his life and death. But for several months, I had been under attack from members of the Egyptian press, who asked why we were disturbing the king again. I had explained to the media that a CT scan, which is non-invasive and would not damage the mummy, would help us solve the mysteries surrounding Tutankhamun’s life and death. But there were still people watching me carefully, hoping for a disaster. I knew that there was no room for error, so I was not looking forward to the next day with my usual excitement.

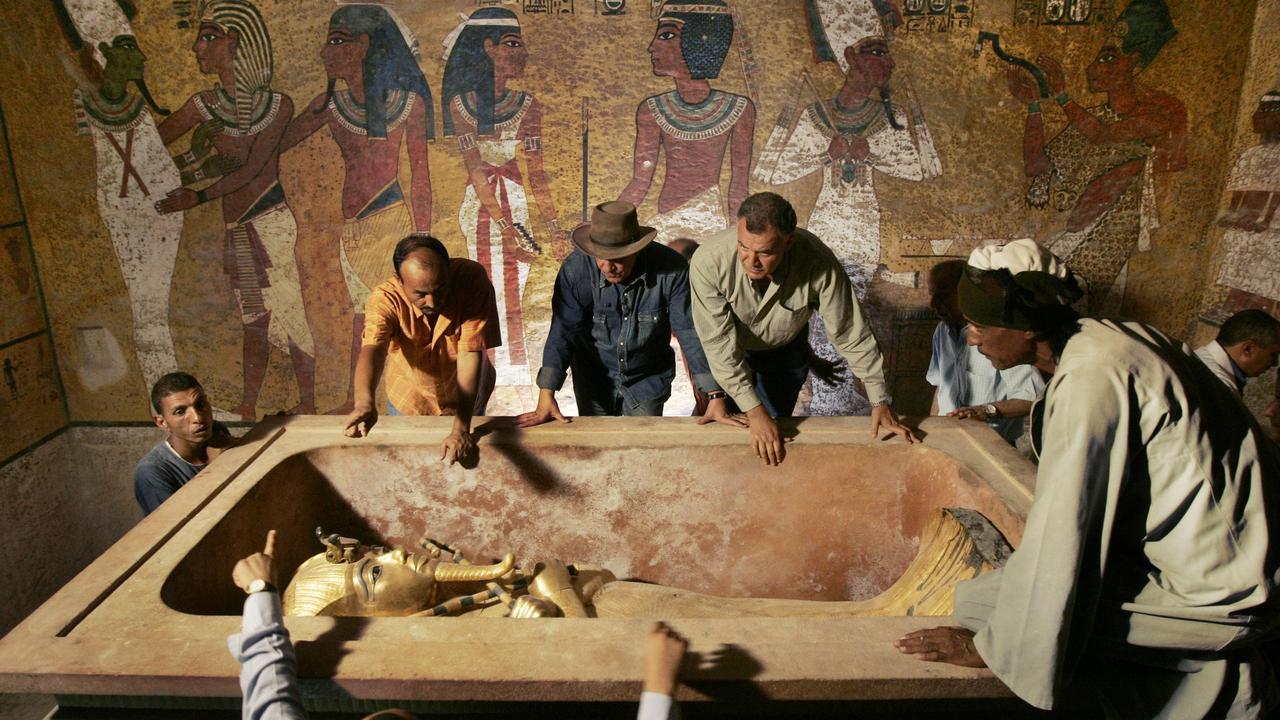

Imydwat, first hour: detail; Osiris, Tutankhamen and his ka; Nut greeting Tutankhamen; Tutankhamen as Osiris from Opening of the Mouth ritual; outer coffin in quartzite sarcophagus. Photo: Francis Dzikowski

I arrived at the Luxor airport on the morning of January 5th wearing my excavation Jeans and denim shirt and my famous hat. Some tourists recognized me and asked what new discovery I was going to make. I just smiled and got into my car. We went to my hotel, and I stayed in my room from 8 am until the afternoon, when the tourists would be leaving the Valley. I was so nervous that I turned all the phones off. At 4:30 pm I went to the hotel lobby and found my team waiting for me: Sabri Abdel Aziz, head of Pharaonic Monuments, and other archaeologists, conservators, restorers, and technicians to operate the CT machine. All of them were Egyptian. I felt as I was going to meet the living king, and that he would ask me personally to take good care of him. I knew I had to make sure that the job was done perfectly: I had to keep the king safe.

We arrived at the Valley of the Kings under a gray sky full of clouds. I had tried to keep the date of the examination secret, because I did not want to have thousands of people around me to disturb the king. However, I had made arrangements with the Egyptian media allowing them full coverage of this event. I did not want to make the mistake that Carter made in 1922 when he gave exclusive rights to the London Times and stopped the Egyptian press from visiting Tutankhamun’s tomb. As a result, Minister of Antiquities Morcos Hana banned Carter for a year from his greatest discovery. The Egyptians were happy about this and marched in the streets saying, “Viva Morcos Pasha Hana, Minister of Tutankhamun.” This January, there were representatives of local Egyptian newspapers in the Valley. There were also print and TV journalists from the National Geographic Society, who knew about the scan because their organization had, together with Siemens Ltd., donated the CT machine to Egypt. But to my surprise, French and Japanese TV had also been told about the secret day, and were waiting for me near the tomb.

The TV crew asked me for an interview. After I finished, a big storm came up and it began to rain. I began to worry because the CT scan machine was outside the tomb and we would need to bring the mummy out to it, which we could not do in bad weather.

I heard people whispering about THE CURSE. I have never believed in the curse. I have even written a book for children showing that there is no curse. However, the rainstorm made me nervous, especially on top of the phone call I had received on the way to the Valley from my sister, telling me her husband had just died. But I tried to put this all out of my mind and concentrate on my work.

I entered the burial chamber of King Tut with my team and warned the TV crews to be quiet or I would dismiss them all. My team knew the plan and we immediately put it into action. First we took the glass cover off of the sarcophagus. When I looked inside I saw a most beautiful face–the gilded wooden outer coffin of Tutankhamun. The cobra and vulture protected his forehead, and his golden hands grasped the crook and flail, important symbols of kingship, against his chest. I saw that the gold on the coffin was cracking and instructed my head of conservation to make restoration of the lid her top priority. Then we brought in ropes and put them under the lid at the head and the foot. We began slowly to lift it out.

The mummy itself lay inside the coffin where Carter had left it in 1926, in a wooden tray filled with sand. The body was covered from head to foot with a white cloth, so I could not yet see the face of the king. First we needed to take him out of the coffin. If anything were to go wrong for example if we dropped the mummy, I could lose my job. Everyone was waiting to see what would happen. I was nervous, but I knew it would be fine, because I have trained all my life to take care of the pharaohs.

Egypt’s former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, Dr. Zahi Hawass supervises the removal of King Tut from his stone sarcophagus in his underground tomb in the famed Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. Photo: news.com.au (AP)

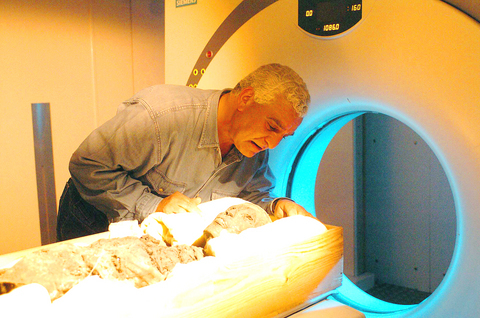

Dr. Hawass readies the mummy for the scan. Photo: Taipei Times

We brought the wooden tray to the top of the sarcophagus and the moment finally came when I was to be face to face with the boy king. I pulled back the shroud of linen that lay over his face and gazed down at the once-mighty pharaoh. I felt as if I owned the world. But I knew that the mummy was in bad condition–during the embalming and funeral ceremonies, the king had been covered with unguents and resins that had hardened and glued him to the inner coffin and golden mask. Carter and his team had cut the body into pieces to remove it from the coffin and used hot knives to take the head from the mask. Further damage had been done when the artifacts (about 150 of them) were removed from the wrappings. But I was still shocked when I looked closely at the mummy. It was in terrible condition. The ribs were gone, and the linen bundles in his chest looked like rocks. I believe that Carter left the mummy inside the tomb because he did not want anyone to see it like this. Many stories and rumors had circulated about the mummy, but now we were seeing the truth.

Lying on the body was a card left originally by Carter, telling the history of the mummy’s examinations. The first time the mummy was viewed was November 11, 1925, by Carter and his scientific experts: Douglas Derry and Saleh Bey Hamdi. The second time was by R.G. Harrison, who x-rayed the entire body in 1968. The next time was in 1978, when J. Harris X-rayed the head. And now we were here, to continue the story.

Carter’s team had concluded that the king was about 5 and a half feet tall, lightly built, and had died between the ages of 18 and 22. They had noted various details, including a fracture of the left thigh and a detached left kneecap, but had no suggestions about the cause of Tutankhamun’s death. From Harrison we had learned that there was embalming material in the cranial cavity, along with a loose fragment of bone. Harrison also saw an anomalous area on the back of the skull, which he suggested was evidence for a blow to the head.

Perhaps, he said, King Tut was murdered. Others had picked up on this suggestion, and murder theories abounded. Harrison also noted that the sternum and many of the front ribs were missing. He could not tell if this had been done by Carter or he ancient embalmers, but others wondered if this was evidence for an accident that had crushed the young king’s chest. What looked like a partially healed lesion on the left jaw was also linked to this hypothetical accident-perhaps a fall from his chariot? This team confirmed an age at death of between 18 – 22 vears. The results of the 1978 X-rays of I.E. Harris were never published. although this team of dentists suggested that the king had been in his twenties when he died.

What would we learn from this new investigation? I was hoping to find out more about Tutankhamun’s life, and perhaps settle the question of whether or not he had been murdered. The actual scan took about half an hour, although a technical glitch (sand in the cooling system) delayed us for almost an hour. Egyptian CT specialist Han Abdel Rahman operated the machine, taking over 1,700 images of the body.

When Dr. Hani had finished, we put a new card about this examination on the king’s chest and carefully laid him back in his tomb. I returned to Cairo, where I had a carefully selected team of Egyptian radiologists, anatomists, and forensic specialists, under the leadership of Dr. Mirvat Shafiek of Cairo University, ready to study the scan. I gave them two months to work. Near the end, we brought in three internationally-recognized authorities to join the team, so that the results would have international status. The scientists met together over the course of two days, on March 4th and 5th, to review their conclusions. These were some of the best scientific meetings I have ever witnessed. Everyone knew his or her business, and discussion was lively and productive.

The scientists concluded that the king had been well-fed and generally in good health for most of his life. His bones showed no signs of childhood malnutrition or infectious disease. They agreed that, according to modern tables, he was around 19 when he died. He had an impacted wisdom tooth that might have been painful, but would not have been life-threatening. They also noticed that he had a slight cleft in his hard palette, but this would probably not have had an external manifestation, like a harelip. A bend in his spine might be a slight scoliosis, but also might just be the way the embalmers laid him out.

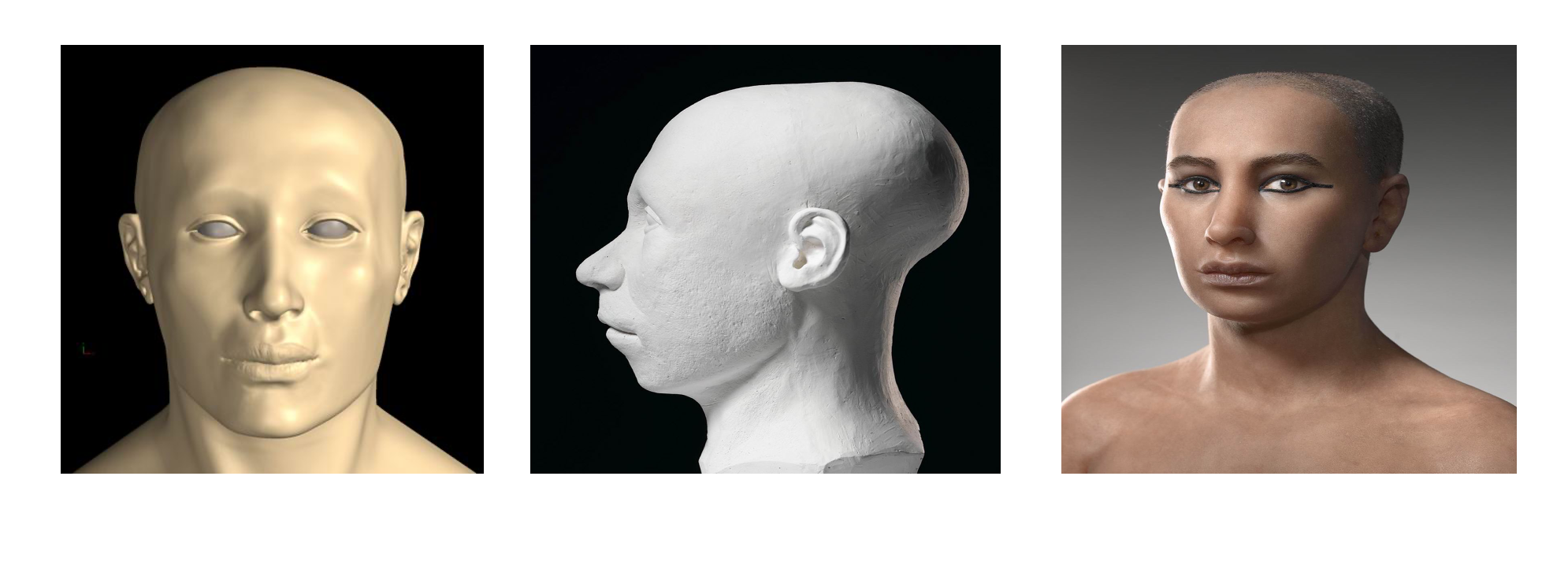

Reconstructions were done of the King’s face by three independent teams from (left to right) Egypt, the United States, and France. Photo: Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt and National Geographic Society

There was no “cloudy” area on the skull, and no evidence at all that he had suffered a blow to the back of the head. In fact, there is no evidence that he was murdered, although it is possible that he was killed in a way that doesn’t show up on the CT scan (such as poison). The most interesting thing that the team noticed was that there was a fracture of the king’s left thigh, just above the knee, something from which Carter’s team had drawn no conclusions. But based on the fact that this is a typical type of fracture for a young man of Tutankhamun’s age, the scientists feel that this could be evidence for an accident. Some of the scientists also saw what they considered evidence that the bone had begun to react to the damage, suggesting that the king lived for between one and five days after the break. The left knee-cap is totally detached (and, in fact, was mistakenly wrapped, presumably by Carter’s team, with the left hand), and there are other smaller fractures that may be connected to such an accident. A broken leg could not have killed Tutankhamun, but he could have developed an infection and died from that. It is also possible that the leg was broken by the embalmers. However, the CT scan shows that there is solidified embalming fluid in the break, so they would have had to break not only the bone, but also the skin. Thus we can draw no firm conclusions about Tutankhamun’s death from the results of the CT scan, but it does give us more information about the boy king.

The scan has also been used by several independent teams-one French, one American, and one Egyptian-to do reconstructions of the king’s face. The Americans worked blind, without any information about the identity of their subject. The faces the three teams came up with are all similar, yet also different. All have the same shape to the face, and the bizarrely elongated skull seen in the CT scan, along with the slightly undershot chin and the buck teeth of the Tuthmosid line. The size and shape of the eyes are also the same in each version. It is the noses and the overall effect that is different in each version. The French version has the most personality, perhaps because the artist has added skin and lip color, glass eyes, and hair, but to me the Egyptian team came the closest to how I think of Tut.

Despite my apprehension, the scanning of Tutankhamun was a great success. The mummy is back. safe in his tomb, and we have more pieces to the puzzle that was his life and death. But all the questions have not yet been answered and so we will keep searching for the truth. The mystery will continue.