Egyptian Jewelry: A Window into Ancient Culture

Ancient Egypt is often described as a relatively stratified society. However, one element available to every Egyptian – from the youngest child to oldest priest, from the poorest farmer to pharaoh – was jewelry. From the predynastic through Roman times, jewelry was made, worn, offered, gifted, buried, stolen, appreciated and lost across genders, generations and classes. Egyptians adorned themselves in a variety of embellishments including rings, earrings, bracelets, pectorals, necklaces, crowns, girdles and amulets.

Because jewelry was so universal and pervasive we can learn a vast amount from studying even a single bead. Yet much of the ancient jewelry pieces in modern collections, especially those gathered in the 19th and early 20th centuries, have little to no recorded archaeological context – meaning they lack critical information for full understanding. These pieces also have often been trivialized as purely aesthetic rather than informative, marginalizing the potential and importance of studying jewelry. Instead of being dismissed, jewelry should be used as scholarly objects to better understand ancient Egypt. Burial trends, ritual practices, manufacturing skills and resource and material availability are just a few avenues to explore through jewelry. Such study, in turn, can provide essential information on a range of topics, including trade, gender, class, economics, military power and political authority.

For Egyptian jewelry, styles, material choices, fabrication techniques and even object type and decorative meaning changed over time. Gemstones such as lapis and turquoise were imported and thus often less available during unstable political periods. Meanwhile, some locally available materials were popular only during certain periods: Purple amethyst was the rage during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055-1650 BCE), while glass was used in some 18th-dynasty royal and elite jewelry, such as King Tutankhamun’s pectorals and inlaid mummy mask.

Most Egyptians wore some type of jewelry during their lifetimes, and almost every Egyptian was buried with some form of adornment. The materials chosen and the quality of workmanship often marked the status of the owner or wearer. The elaborate gold masks and inlaid pectorals of the 21st and 22nd-dynasty kings of Tanis (ca. 1069-945 BCE) and the intricate Middle Kingdom princess girdles and bracelets from their burials at Lahun and Dashur were of far different quality than a simple strung clay bead found in a poor individual’s burial. Some simpler objects such as single strung barrel-shaped carnelian swr.t beads were also common in elite burials.

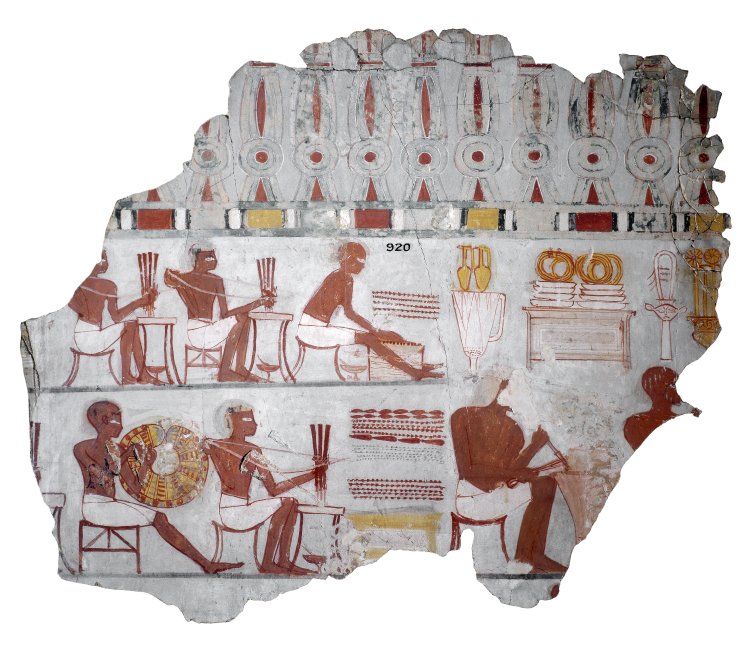

Regardless of quality, these were objects of display, protection and power. Most excavated jewelry comes from tombs or from a few temple foundation deposits. Aside from the objects themselves, we can learn much from texts and images describing and depicting adornments. In fact, some jewelry types are known only from depictions on statues and reliefs. A few Egyptian jewelry workshops have been excavated, but most of what we know about ancient craftsmen and their techniques comes from tomb scenes. In the New Kingdom, tomb scenes of Sobekhotep and Rekhmire, some workmen drill beads with quadruple and triple bow drills while others string beads.

Jewelry was both decorative and purposeful. One bead may reveal much, especially if archaeological context is known. Its material – ceramic, metal, certain stones – can potentially be sourced and origin thus understood. Scientific analysis, such as LA-ICP-MS (laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry) and x-ray florescence, allows for compositional analysis and comparisons. Even the exact gemstone quarry or the precise location of Nile clay can sometimes be identified. Examining a bead under a microscope can also yield clues regarding composition and use. For example, glass and glazed objects often produce visible bubbles; if a bead’s piercing shows signs of wear, it probably was worn and displayed before final deposit in a burial. Some jewelry was made strictly for burial, and bracelets and other adornments have been found simply laid on mummies without being fastened.

Jewelry often held apotropaic powers for its wearer – both living and dead. Color and material were significant, protecting the living from disease and danger and, wrapped within a mummy’s bandages, guarding the deceased for eternity. The Book of the Dead, the famed New Kingdom funerary document, prescribes specific materials for certain amulets and often detailed where on the body to include them. Chapter 156 called for red jasper for the girdle tie of the goddess Isis, which was placed on the throat of the mummy. Chapters 159 and 160 assigned green feldspar for papyrus amulets, and Chapter 30 prescribed what is believed to be green jasper for the heart scarab. The heart scarab amulet was created to aid the deceased in the weighing of the heart ritual in which the justice of one’s heart was weighed against the feather of truth/Maat.

Kings bestowed favor and military honors through jewelry. Based on excavated examples from Nubia, pierced and polished oyster shells inscribed with the cartouche of King Senwosret I were probably worn by soldiers in the Middle Kingdom. In the 18th dynasty, fly-shaped “Golden Fly” pendants or “The Order of the Golden Fly” were given as military rewards. Three large gold flies were found in the burial assemblage of Queen Aahhotep, mother of 17th-dynasty King Ahmose and grandmother of King Amenhotep I, the founder of the 18th dynasty. She was lauded in Ahmose’s Year 18 Karnak stela as a great warrior who fought against the rebel Hyksos, and her gold flies are further evidence of her military prowess.

In relief at the Karnak Temple, king Thutmosis III listed and depicted the many rich gifts, including jewelry, he collected from his foreign campaigns and then bestowed to the god Amun-Re. The campaign and general wealth from Thutmosis’s reign is also reflected in the rich burial of three of his queens. The tombs of the “foreign queens” include necklaces, girdles, bracelets and crowns; pieces like this diadem have non-Egyptian motifs, supporting other evidence that these women were foreign-based.

While kings usually bestowed gold flies and shebyu necklaces during prosperous or victorious times, jewelry types can also reveal information about less stable political and economic situations. Jewelry is small, transportable, often valuable and was thus usually the first item to be snatched during tomb robberies, particularly in antiquity. To varying degrees throughout Egyptian history, metal adornments on mummies and in assemblages were illegally collected to be melted down and recast. Ancient records, like the late-New Kingdom Amherst Papyrus, and P. BM 10068 detail the crimes of 20th-dynasty tomb robbers in Thebes. Based on these and other texts, it seems jewelry robberies increased and became more strategic as political centralization decreased towards the end of the New Kingdom.

Jewelry even can counter conventional wisdom. Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1069-664 BCE) openwork faience spacer beads include complex designs, which demonstrate exquisite skill. These were made during a period traditionally dismissed as declining and even chaotic politically and socially. But these beads suggest a different narrative. The royal and religious themes of these beads were once reserved for temple walls, and this change of medium demonstrates a change in religious beliefs – or at least in religious decorum. By demonstrating artisans’ sophisticated skills, they are further evidence of the need for nuisance when studying and describing this complicated period in Egyptian history.

Throughout ancient Egypt, jewelry was offered at temples, buried in tombs, stolen from mummies, presented as gifts and rewards, and worn to the temple and tomb, as well as to the marketplace. Small, sometimes valuable and often intricate, jewelry presents intimate and important ways to study Egyptian culture.

Recommended Reading

Andrews, Carol. Amulets of Ancient Egypt. London: Published for the Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press, 1994.

Andrews, Carol. Ancient Egyptian Jewelry. New York, Abrams, 1991.

Bianucci, Raffaella, Michael E. Habicht, Stephen Buckley, Joann Fletcher, Roger Seiler, Lena M. Öhrström, Eleni Vassilika, Thomas Böni, and Frank J. Rühli. “Shedding New Light on the 18th Dynasty Mummies of the Royal Architect Kha and His Spouse Merit.” PLoS One. 2015; 10(7): e0131916. Published online 2015 Jul 22: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4511739/

Brand, Peter. “The Shebyu-Collar in the New Kingdom, Part 1,” Studies in Memory of Nicholas B. Millet, The Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquity Journal 33 (2006), 17-28.

Cifarelli, Megan. “Adornment, Identity, and Authenticity: Ancient Jewelry in and Out of Context.” Review Article on Masterpieces of Ancient Jewelry: The Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, February 13-June 4 2009, in the American Journal of Archaeology Online Museum Review, Issue 114, January 2010, pp. 1-9.

Gestoso, Singer, Graciela N. “Queen Ahhotep and the ‘golden fly’.” Cahiers Caribéens d’égyptologie 12 (2009): 75-88.

Harrell, James. “Gemstones.” UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2012.

Lilyquist, Christine, with contributions by James E. Hoch and A.J. Peden. The Tomb of the Three Foreign Wives of Thutmose III. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

Meskell, Lynn. “Individuals, Selves and Bodies.” In Archaeologies of Social Life: Age, Sex, Class et cetera in Ancient Egypt, 8-52, Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

Miniaci, Gianluca, Susan La Niece, Maria Filomena Guerra and Marei Hack. “Analytical Study of the first royal Egyptian heart-scarab, attributed to the Seventeenth Dynasty king, Sobekemsaf.” The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin vol. 7 (2013): 53-60.

Nicholas, Paul T. and Ian Shaw, eds. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Schorsch, Deborah. “Gold in Ancient Egypt.” Metropolitan Museum Online, 2017.

Schorsch, Deborah. “The Tomb of Wah.” Metropolitan Museum Online, 2004.

Troalen, Lore G., Jim Tate, and Maria Filomena Guerra. “Goldwork in Ancient Egypt: workshop practices at Qurneh in the 2nd Intermediate Period.” Journal of Archaeological Science. Volume 50, October 2014, Pages 219-226.

Xia, Nai. Ancient Egyptian Beads. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.