Demotic: The History, Development and Techniques of Ancient Egypt's Popular Script

When most people think of ancient Egyptian scripts, they think immediately of hieroglyphic writing, the pictorial script that has fascinated non-Egyptians for thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians devised this “picture writing” in their predynastic period, with the earliest examples known found in an elite chamber in Abydos, Tomb U-J, which dates to around 3200 BCE. Along with these iconic hieroglyphs, Egyptian scribes also established a more cursive method – hieratic (priestly) script. This style adapted the essentials of hieroglyphic signs but was intended for more rapid writing with ink on surfaces such as pottery and, especially, papyrus.

At first, hieroglyphs and hieratic were used mostly to write individual words, including names of persons, places or commodities. By the third dynasty (about 2686 to 2613 BCE), the scribal skills and traditions for hieroglyphic script were fully developed, allowing complete, continuous prose. Egypt’s literary tradition was born and soon to produce religious works such as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and Book of the Dead; great fictional tales like the Middle Kingdom Story of Sinuhe; important autobiographies, like those of Weni and Harkhuf in the sixth dynasty and of Ahmose, the Son of Abana, in the 18th, and more.

Those literary traditions continued until roughly 650 BCE, when hieratic began a rapid evolution that resulted in two new scripts: the short-lived “abnormal hieratic” of Upper Egypt and the more durable “Demotic” of Lower Egypt. It was not long before Demotic had become the dominant script of everyday business in Egypt – never completely supplanting hieroglyphic and hieratic but, over time, relegating those older scripts to religious, ceremonial or emblematic functions.

In Egyptology, Demotic was traditionally a poor stepchild to the older scripts, appealing to only a handful of scholars. Champollion himself never mastered it. The first expert to unlock the mysteries of Demotic was the German, Heinrich Karl Brugsch, who published Egyptology’s first systematic grammar of Demotic in 1848 – a generation after Champollion’s 1822 breakthrough in deciphering hieroglyphic translations. Demotic acquired a reputation of being extremely difficult to learn, which discouraged students from tackling it. Demotic also suffered from its association with long centuries of Egyptian “decline,” originating some 400 years after the end of the mighty New Kingdom. The new script flourished only when Egypt found itself under the domination of foreign empires: Persians, Greeks and Romans.

Indeed, until the 1950s and 1960s, few Egyptologists showed much interest in those last centuries of ancient Egyptian history or in using Demotic to study them. Since the 1970s, however, and especially since the 1990s, Demotic studies has made a comeback as younger scholars realized the promising extent of material and the resulting opportunities for exciting, original work.

But why did Egyptian scribes feel the need to create Demotic? Why did they adopt it over a hieratic script that had served their needs for centuries? The first clue toward answers is the meaning of “hieroglyphic” itself – Greek for “sacred carvings.” The Egyptians themselves called their hieroglyphic script the Medut Netjeru (the Words of the Gods) and thought it had been created by the scribal deity Thoth. As a result, young scribes were not only taught the proper forms of written signs but also encouraged to produce texts in the prestigious, Middle Egyptian language of the Middle Kingdom, long after Middle Egyptian had ceased to be a spoken, everyday language.

At the same time, hieratic began to diverge from hieroglyphic conventions. By the late 18th dynasty (around 1300 BCE), scribes began writing many everyday documents in their vernacular – what is now called “Late Egyptian.” One possible explanation for Demotic’s split from hieroglyphic and hieratic is that, by 650 BCE, the language that Egyptians actually spoke was almost intolerably different from Middle Egyptian and even noticeably different from Late Egyptian. By this period, scribes may have more and more associated hieratic with obsolete linguistic forms, and it may have seemed to them silly or counterproductive to write everyday documents in a language centuries out of date. When younger, more adventurous scribes wrote in their own vernacular, they may have felt increasingly free to ignore many of the rules and conventions of hieratic writing, just as they also ignored the old grammatical rules and vocabulary restrictions of Middle Egyptian and Late Egyptian. Demotic, a truly “popular” script, was born and began to evolve swiftly.

Egyptians themselves soon called this new script the sekh shat, or “documentary script.” The term “Demotic” was coined by Greek historian Herodotus, who introduced readers to the variety of scripts he encountered in fifth-century BCE Egypt:

The Greeks write and calculate by moving the hand from left to right; the Egyptians do contrariwise; yet they say that their way of writing is ‘rightward,’ and that the Greek way is ‘leftward.’ They use two kinds of writing: one is called sacred (ira), and the other common (demotika).

Here, Herodotus enjoys a little joke, a pun on the meanings of “right” and “left” that he might have heard from a Greek-speaking Egyptian. When Herodotus wrote that Egyptians claimed to write “rightward” even though they moved their writing hand toward the left, he really meant that they claimed to write “correctly” (“rightly”). From the Egyptian perspective, the Greeks wrote “incorrectly” (“leftly,” in the sense of “gauchely” or “maladroitly”) by moving their writing hands toward the right. In his comment, Herodotus also combines hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts, correctly recognizing they are two variants of the same Medut Netjeru. But he also knew that Demotic was the truly “common” or “popular” script.

Fundamentally, Demotic is similar to late hieratic: a largely consonantal script, with vowels used only in limited circumstances. Also, like the hieroglyphic/hieratic system, Demotic used both phonetic signs (which might indicate one, two, three or even more consonants), as well as non-phonetic signs (called determinatives or classifiers), which indicated the sense or category of a word and to identify a word’s end. In the developed system, many Demotic signs can be traced to individual hieroglyphs. However, many individual Demotic “signs” are actually “ligatures,” that is, cursive groups derived from two or more hieratic signs. Many of these Demotic ligatures originate in what is called “group writings” – standardized sequences of two or three signs, usually with a “strong” consonant plus one of the “weak” consonants or semi-vowels of Egyptian.

This “group writing” had originated at least as early as the Middle Kingdom, often, but not exclusively, to spell foreign words. By the later New Kingdom, the process was increasingly preferred not only for foreign words but also for Egyptian vocabulary. This evidently reflected sound changes and pronunciations that older, one-consonant signs could no longer represent. While evidence indicates that that group writings sometimes were used for a syllable (i.e., a consonant plus a vowel, indicated by the “weak” consonant in the group), groups in the later New Kingdom increasingly represented only the “strongest” consonant in the group (i.e., in a group like b + w, the w might be ignored). This technique became typical in Demotic, where a number of these groups were taken over as fully “alphabetic” signs to write only a single consonant. Meanwhile, many Demotic ligatures became visually indistinguishable from one another in isolation. This may have allowed faster writing, but actual sound values of many Demotic ligatures became recognizable only in the context of a larger word.

Most important, while hieratic and hieroglyphic were always closely connected to each other and, in theory, were always convertible to each other, spelling conventions in Demotic quickly diverged from widely hieratic. As an academic exercise, experts can identify the hieratic origins of most Demotic signs and even convert Demotic spelling into hieroglyphs. But the result is often a spelling that no Egyptian scribe would ever have used for the older hieratic or hieroglyphic.

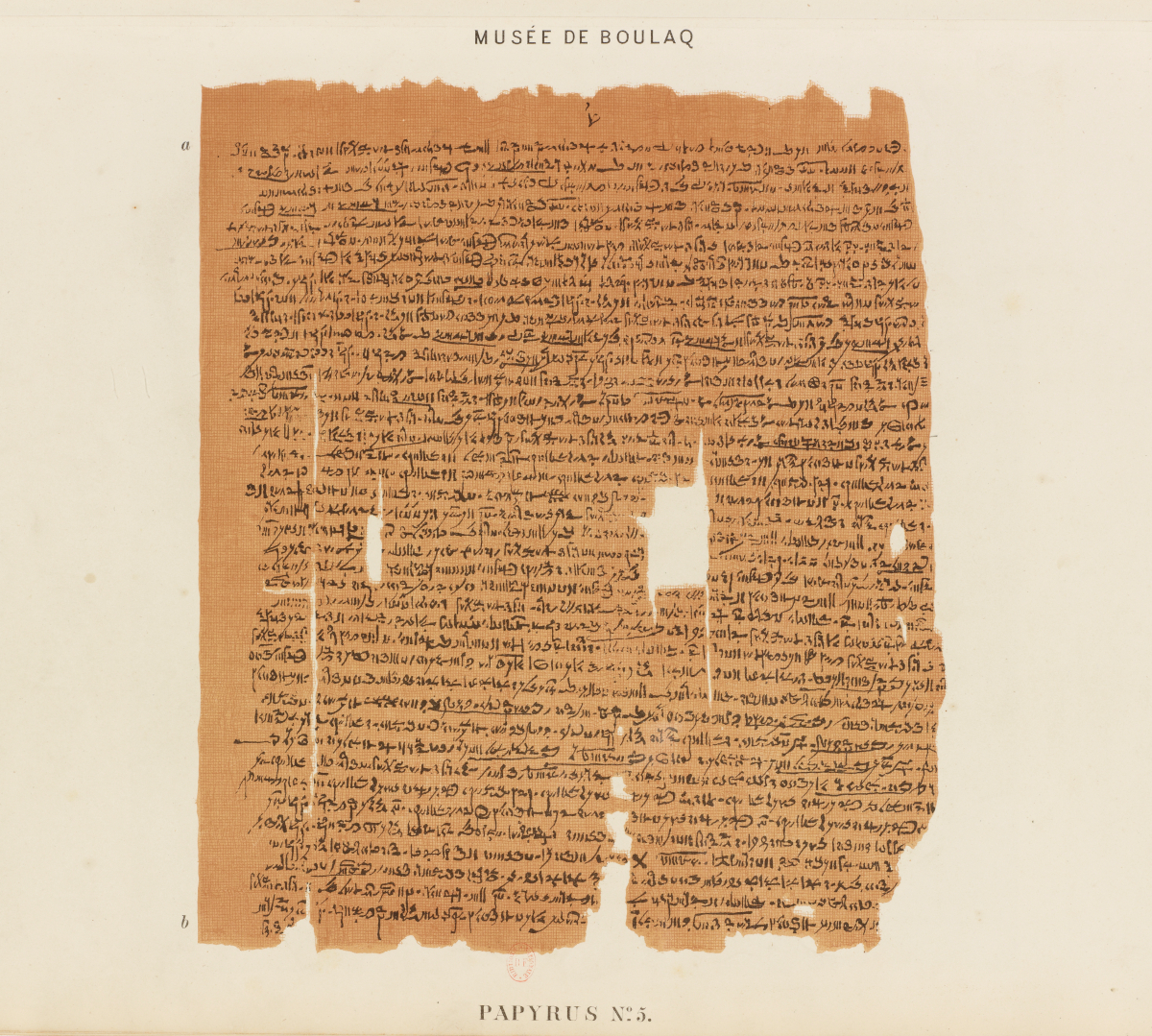

Writing continued to evolve as Egypt itself changed. Two centuries after Herodotus’ sojourn, Alexander the Great conquered the Land of the Nile (332 BCE). When Alexander died in 323 BCE, Egypt was left in the hands of his general Ptolemy, and the resulting Ptolemaic period did not end until the 30 BCE death of Cleopatra VII. During these years, Demotic continued to grow and flourish. Many thousands of Demotic texts are known, including everyday documents like real estate contracts, marriage records, personal letters and wills. But Demotic also came to be used for more prestigious texts, including sacred and secular literature.

In fact, even as Egypt fell under foreign domination, its literary tradition flourished. Perhaps the greatest Egyptian work of literature of the period – indeed, perhaps the greatest tale in Egyptian history – is the Demotic First Tale of Setne Khaemwas, a ghost story set in the 19th dynasty. The tale involves a contest between Setne Khaemwas, the legendary persona of an actual son of Ramses II, and the ghost of a fictional prince from the distant past (a certain Naneferkaptah). The contest was over a magic book said to have been written by Thoth himself. When this story was first translated by Heinrich Brugsch in 1867, it created a sensation and was repeatedly adapted by popular authors, ultimately contributing to the modern tradition of “mummy” fiction and films.

After the Roman Empire took over Egypt in 30 BCE, Demotic continued to be taught and used, but its importance gradually diminished. Under the Ptolemies, Demotic had been a recognized vehicle for binding contracts; Romans increasingly insisted that legal documents be written in Greek. Yet many great works of literature are known from Roman-period Demotic texts, and enough people knew the script to leave substantial Demotic graffiti at sites across Egypt!

By the middle of the third century CE, the Roman government seems to have ceased financial support for Egyptian temples, where boys previously received advanced training in traditional scripts. And as the first millennium continued, more Egyptians became Christians and appeared to have lost interest in traditional Egyptian education. In the end, the last toehold for both hieroglyphic and Demotic seems to have been beyond Egypt’s southern border: Nubians continued to use the script as they worshipped traditional Egyptian gods even as temples in Egypt and throughout the Roman world were shut down. The last known, datable inscription in one of Egypt’s native scripts is a 452 CE Demotic graffito from the temple of Isis at Philae. Unfortunately, this historic text reportedly is covered today by the base of a large light fixture for the Philae Temple’s Sound and Light Show! One can hope the graffito is safe under its covering and that, at some point, its words will again be revealed – a message from a scribal tradition that began 3,650 years earlier at Abydos.