Cleopatra the Great: Last Power of the Ptolemaic Dynasty

The famous scene of Cleopatra emerging from an unrolled rug, popularized by playwright George Bernard Shaw, is based on an ancient account but tweaked for dramatic effect. The anecdote is one example of many contrasts between this famous queen’s image and her life as we know it today. In truth, Cleopatra enlisted the services of a trusted servant to carry her, bundled in dirty laundry, past palace guards and into Julius Caesar’s presence.

Cleopatra must have been petite to be so concealed and carried. The popular belief that she was an exceptional beauty is a narrative based on ancient sources. Cleopatra VII was identified with the Egyptian goddess, Isis, who is equated with Aphrodite and Venus. During her sojourn in Rome, Caesar dedicated a golden statue of the queen in the temple of Venus. The comparison implies Cleopatra VII must have resembled the classical goddesses of love. But unlike the image portrayed most noticeably by actress Elizabeth Taylor in the famous 1963 film, Cleopatra, I envision Cleopatra VII as a wiry, small-boned woman – a picture supported by numismatic images and at least one posthumous Pompeian wall painting.

Following the death of her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, Cleopatra ascended to the throne in 51 BCE with one of her younger brothers as co-regent. The 18-year-old queen found herself embroiled in court intrigue and soon was ousted from Alexandria, the capital of her realm. She gained support from the Roman ruler, Caesar, and the pair defeated her brothers and their supporting coteries. From that moment until her death by suicide almost 20 years later, Cleopatra VII ruled her kingdom with little sedition or revolt, although she had to contend with the expansion and power of Rome.

The queen’s command of language and magnetic personality attracted all those in her presence. Cleopatra VII was literate in ancient Egyptian and conversed with Aethiopians, Troglodytes, Hebrews, Arabians, Syrians, Medes and Parthians in their native languages. The sound of her voice was compared to a melodious, multi-stringed musical instrument. In addition to her linguistic skills, the ancients praised her intellect and ascribed to her treatises on such diverse subjects as cosmetics, coinage, chemistry and gynecology.

Documented monetary reform supports the ancient tradition that Cleopatra VII wrote treatises on coinage and on weights and measures. She strengthened her nation’s economy by making explicit the fiduciary nature of the bronze coinage in circulation, the value of which was determined by Cleopatra and not based on weight. The result of this reform approximated the value of her bronze coinage to the Roman denarius, the contemporary currency of choice throughout the Western world.

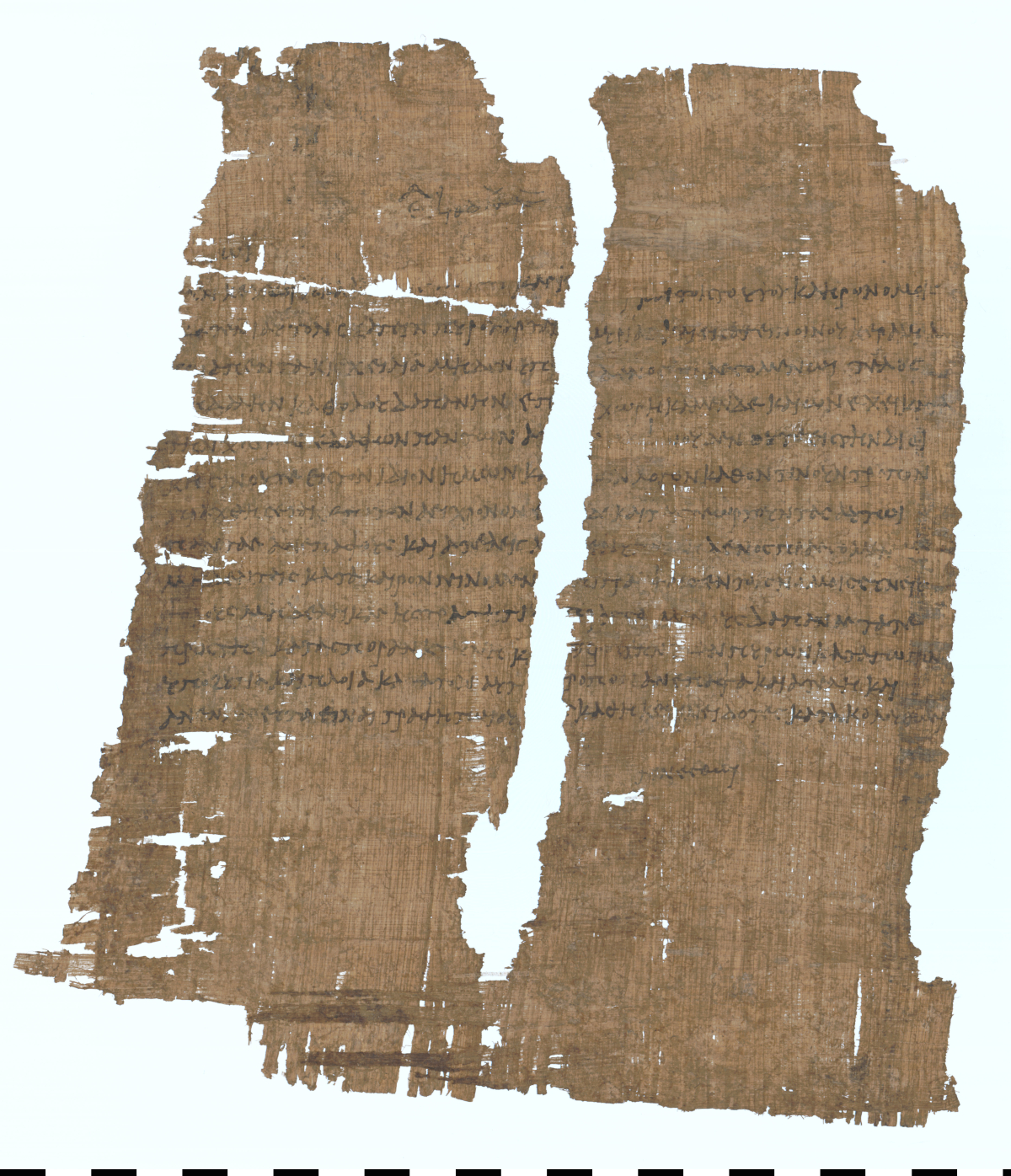

The queen played an active role in the administration of her realm, confirmed by a papyrus written in Greek. That document, like a present-day inter-office memo, was written to Cleopatra VII by a high-ranking Alexandrian court official. It contains an annotation in Greek, “Make it happen!,” that is attributed to Cleopatra herself. While not exactly an autograph, the subscription is a rare example of a note handwritten by an ancient monarch.

The remarkable events of Cleopatra’s life include a child with the later-assassinated Caesar, plus her marriage and children with the Roman, Marc Antony. Antony and Cleopatra’s forces were defeated by Octavian’s army at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and assured the end of her reign. The queen’s suicide at age 39 is the stuff of legend. Tradition maintains that she experimented with condemned prisoners to find the most painless lethal poison, and ultimately elected to end her life by venom at a temple to the goddess Isis in Alexandria. Whether she was bitten by one or more serpents may never be determined, but what’s certain is that Cleopatra chose to die for her principles rather than surrender.

Popularists have repeatedly misunderstood the presence and roles of Cleopatra’s manicurist and hair dresser during her final moments. They were not ensuring their queen looked attractive in death. On the contrary, her suicide was a staged ritual by which she strove in death to deprive the Romans of her capture. According to pharaonic Egyptian practices dating back to the third millennium BCE, royal court officials included barbers and manicurists. They collected clipped hair and nails for ritual disposal, lest they fall into hostile hands to the detriment of their owner. In death, Cleopatra VII reaffirmed her command of pharaonic, Egyptian cultural norms.

Cleopatra VII had grown antagonistic with Rome, and literary testimony shows she was subject to scorn, ridicule and hate after her suicide. Her fate was just the opposite in Egypt, where her pharaonic subjects strove to preserve her memory. Her faithful administrator, Archibios, offered the Romans 2,000 talents to save her statues from destruction. And in 373 CE, centuries after her death, the Egyptian priest, Petesenufe, overlaid a statue of Cleopatra with gold. Cleopatra VII was an educated, disciplined monarch whose beneficial reign was long-remembered and cherished by her subjects.