Canopic Equipment: Beauty and Revelations of from Ancient Egypt

Mummies and the processes by which they have been created have long been a source of fascination for the general public. The various artifacts created to house the results of the mummification activities often include wonderful works of art. Among them are the containers used for the internal organs that were usually removed as a key part.

This excluded the heart, which was considered the seat of intelligence, and the kidneys, which were difficult to extract. The remaining evacuated items underwent the same chemical desiccation process as the corpse itself, and when wrapped in linen bandages, sometimes approximated the shape of a fully-wrapped mummy. Of course, because of cost or other considerations, many bodies remained un-eviscerated. But the removal process was clearly regarded as part of the ideal technique and became part of a ‘standard’ burial for ancient Egypt. Thus developed what is now referred to as canopic equipment.

The employment of this term for organ storage is actually the result of mistaken identity. One form of canopic container was the human-headed jar. According to Classical writers, the Greek hero Kanopos, helmsman of Menelaeos, was worshipped at Abu Qir (Canopus) in the form of such a jar. Early travelers to Egypt connected the jars around mummies to this other name and began calling them “canopic.” The name stuck and has been extended to refer to all kinds of visceral containers.

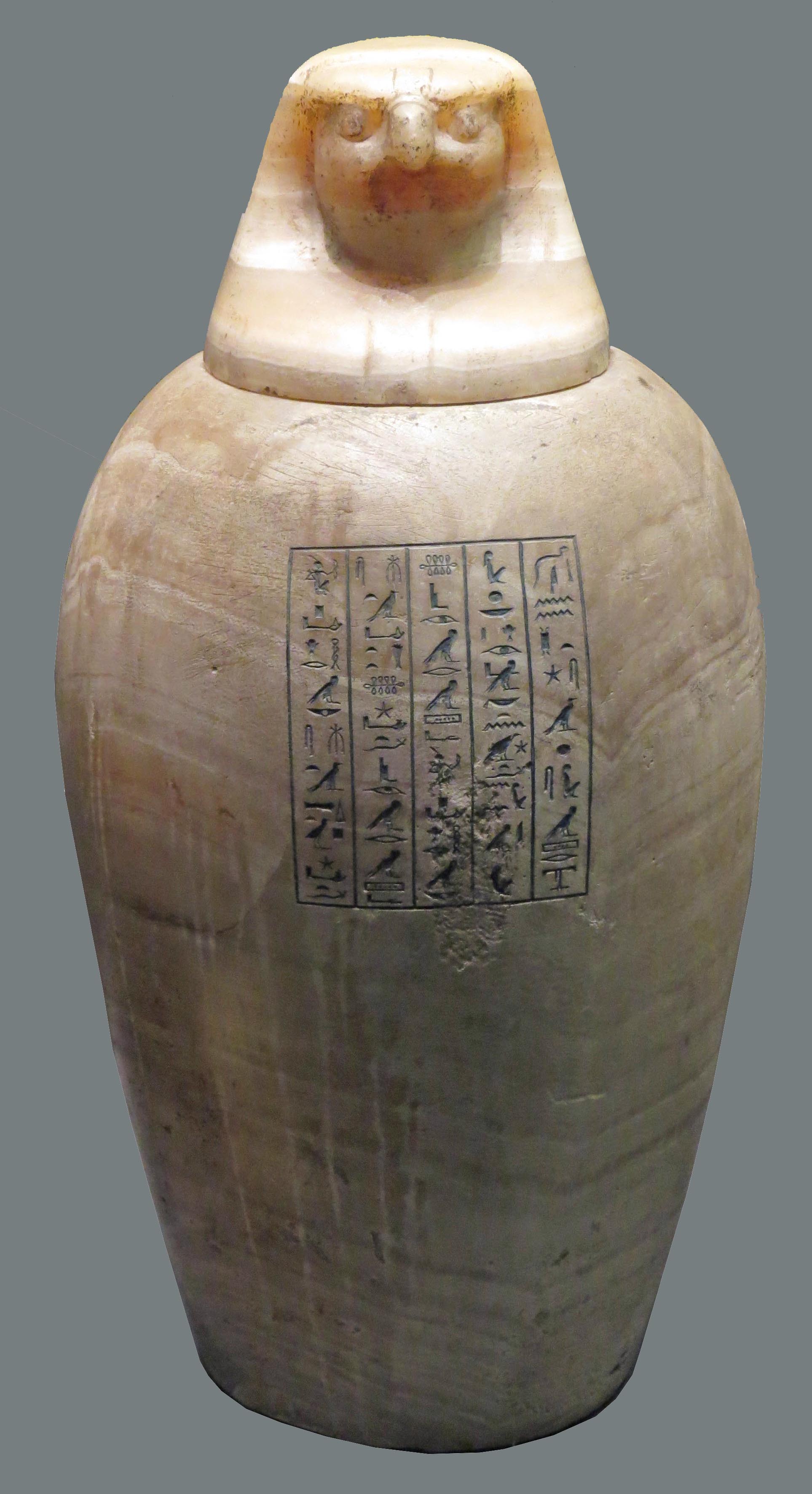

From the late Old Kingdom, the four basic organs removed from a body became associated with specific deities, known collectively as the Four Sons of Horus: the liver with Imseti (later under the protection of the goddess Isis); the lungs with Hapy (protected by Nephthys); the stomach, Duamutef (Neith); and the intestines, Qebehsenuef (Selqet). From the middle of the 18th dynasty, these genii (divinities) were identifiable by their heads: Imseti had that of a human; Hapy that of a baboon; Duamutef, a jackal; and Qebehsenuef, a hawk.

Although embalming is first seen during the late predynastic and early dynastic periods, the earliest items of canopic import date to the beginning of the fourth dynasty, with the cubical, calcite canopic box of Queen Hetepheres, its interior divided into four quadrants. Later, we find burials that included four stone jars with domed lids, probably originally placed in wooden chests.

During the First Intermediate Period, canopic jars started to feature human-headed lids. The image during this period probably represented the dead person rather than the protective deities. But by the end of the Middle Kingdom, a basic “ideal” pattern for canopic equipment had been determined for those who could afford it. A stone outer chest reflected the design of the sarcophagus, with the inner wooden coffin that included bands of texts calling on each tutelary goddess to wrap her protective arms about her genius and proclaim the deceased’s honor. Within the wooden chest were four human-lidded jars, one per genius, with texts repeating the sentiments expressed on the chest. Of course, not all burials conformed to this ideal, but its existence is confirmed in painted representations of the jars, complete with texts, on the inner lid of at least one chest whose size shows it contained only bundles of viscera.

In the 17th dynasty, the anthropoid, rather than traditional rectangular, coffin was widely adpoted in Thebes. Alongside this a new form of decoration arose for the canopic chest that focused on a recumbent figure of the jackal-god Anubis. This trend did not last far into the succeeding New Kingdom, when chest decoration focused on images of the four goddesses and the genii. The form of the chests also evolved, from simple boxes with flat or vaulted lids to imitations of naos-shrines, painted or varnished to match the color scheme of the associated coffin. Chests changed from being predominantly white to black under Thutmosis III, and then to yellow from the late 18th dynasty onward. Initially, jars followed Middle Kingdom patterns, but as the period progressed, more adopted the animal and bird heads of three of the genii, which they now clearly represented.

From the reign of Amenhotep II until the following dynasty, there was a marked divergence between private and kingly practice. The earliest royal chests of the 18th dynasty had been simple naos-form boxes of quartzite, ornamented by no more than texts. However, Amenhotep II commissioned an elaborate calcite confection, with jars carved as one with the fabric of the box, while raised figures of the protective goddesses enfolded each of the corners. This pattern, further elaborated, was followed by kings to at least the early middle of the 19th dynasty. Judging from Tutankhamun’s tomb, such chests had their visceral bundles enclosed in solid gold miniature coffins. Then, beginning in the early 20th dynasty, these “integral” chests seem to have been replaced by separate, over-sized canopic jars arranged against the two long sides of the sarcophagus.

Around the end of the New Kingdom, mummies began to have their viscera returned to the body cavity after embalming. However, so fundamental had the canopic jar become to the funerary outfit that a few high-status individuals were given jars, albeit empty – or even with imitation visceral bundles inside. By the latter part of the Third Intermediate Period, these symbols were superseded by solid dummies – a final triumph of form over function.

“Real” jars – albeit still empty – reappeared at the end of the Third Intermediate Period. These jars were often divided between two half-size canopic chests, placed on either side of the encoffined mummy. Texts on such jars contain new formulations, which are fairly common in the highest status burials during the 26th dynasty but seem to disappear from use by the end of the Late Period. During the Ptolemaic period, canopic equipment is represented by small, tall, naos-form wooden chests, but these disappear by early Roman times.