- Era5th and 6th Dynasty

- Project DirectorDr. Mohamed Megahed

- LocationSaqqara

- AffiliationCzech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University

- Project SponsorAntiquities Endowment Fund

- Project dates2021 - 2022

Written by: Dr. Mohamed Megahed

The era of the pyramid builders still hides many secrets that have not yet been resolved. Most of the sites of the ancient Egyptian pyramids, concentrated in the Memphite region, have been excavated since the beginning of the 20th century – first unprofessionally and later scientifically. Nevertheless, further studies are still needed to clarify many vague aspects.

One of mysterious periods was the reign of King Djedkare Isesi at the end of the 5th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Djedkare came to the throne after a short reign of King Menkauhor, and one of his most important and yet unexplained decisions was to construct his pyramid complex at a completely new area. He selected the site of south Saqqara, which had no earlier pyramids or infrastructure for building the king’s funerary complex. It seems possible that Djedkare decided to choose this site for his pyramid because of its location: it is situated less than 3 kilometers to the immediate west of the temple of Ptah in Memphis (Mit Rahina), the capital city of ancient Egypt at that time.

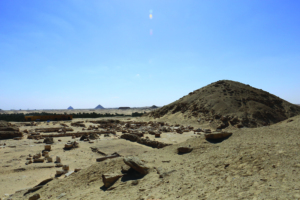

Fig. 1. General view of the pyramid and the funerary temple of Djedkare. Photo: H. Vymazalová

Supported twice by ARCE’s Antiquities Endowment Fund, the Djedkare Project (DJP) mission of the Charles University working at this south Saqqara site was able to find new evidence of Djedkare’s family and officials. In 2018, the mission discovered a large burial ground above the south part of the funerary temple of Djedkare’s queen, and inscriptions with her name, Setibhor, were found here revealing that she was the king’s wife.

Fig 2. General view of the south side of the pyramid and the funerary temple of Queen Setibhor. Photo: H. Vymazalová

In 2021 the DJP team entered the burial chamber in Setibhor’s pyramid for the first time to conduct excavation and documentation followed by conservation and proper protection of her monument. The work of the DJP mission proved Setibhor’s pyramid to be a key queenly monument, which set a trend followed by later Old Kingdom queens.

The monument of Queen Setibhor was briefly explored by Ahmed Fakhry in 1952, who showed that her pyramid was the largest of all Old Kingdom queens, and the temple on the east side contained some royal features. Fakhry also started to explore the inner rooms of the queen’s pyramid but he only reached the entrance of the burial chamber and then stopped the work. The DJP mission in 2021 focused on clearing the entrance to the burial chamber again and continued to uncover the substructure of the pyramid and document its layout. It soon became apparent that the inner rooms of Setibhor’s pyramid suffered bad damage by ancient stone robbers; the side walls, floor, and ceiling of the rooms, once made of fine white limestone blocks, are almost completely missing today.

Fig. 3. The substructure of Setibhor after reaching the floor level. Photo: P. Košárek

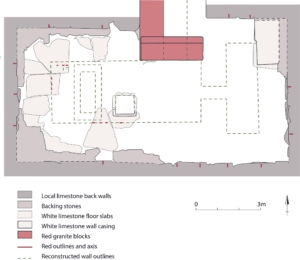

Despite the absence of the original walls, however, the DJP team found indications in the form of red lines drawn by the builders on the core masonry and on the few remaining parts of the floor. With the help of these lines, the DJP team reconstructed the original layout of the interior of the pyramid. It was divided into two spaces: the western side was occupied by the large burial chamber of the queen, while the eastern side contained a smaller room known as the serdab.

The queen’s burial chamber had an entrance at the eastern end of its northern wall, and it was 7.12m long, 2.80m wide, and the height of the walls reached 3.10m. Although the sarcophagus is missing today, its position is indicated by unsmoothed areas on the few preserved floor slabs. A partly preserved canopic pit was situated by the southeast corner of the sarcophagus. The east wall of the burial chamber, today completely missing, used to give access to the east room that represented the serdab. The same layout of inner rooms can be found in pyramid of Sixth Dynasty queens.

Fig. 4. Plan of the substructure of Setibhor. Drawing: H. Vymazalová

The DJP team cleaned and documented the current state of the inner rooms of Setibhor’s pyramid using traditional archaeological methods as well as 3D scanning. The following consolidation and reconstruction works focused on the entire substructure of the pyramid. Starting from the descending corridor and continuing until the burial chamber and the serdab, the preserved masonry was consolidated, and the missing side walls were rebuilt to support a strong modern ceiling protecting the inner rooms.

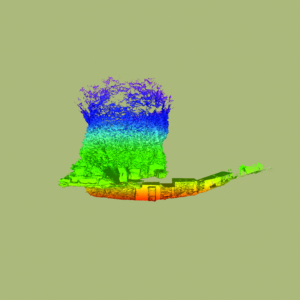

Fig. 5. 3D model of the north-south section of the pyramid of Setibhor. Photo: V. Brůna

Another important part of the Antiquities Endowment Fund project was the continuation of the work in the tomb Khuwy. The DJP team completed the reconstruction of the eastern façade of the mastaba and installed a modern door to protect the chapel and offering chamber with remains of its decoration.

Fig. 6. General view of the antechamber of the substructure of Khuwy. Photo: S. Vannini

The area south of the tomb of Khuwy was also explored, and the mastaba’s south wall was fully cleaned. Less than a meter from this wall, another tomb was found, which was constructed for the king’s oldest son, Isesiankh. Even though it was badly devastated in the antiquity, its architecture still reflects the importance of its owner. The superstructure of the tomb was entered by a monumental portico, situated in the north part of the eastern façade, and leading to several rooms. One of the most significant architectural features of the tomb was a large pillared hall that once included 10 pillars made of white limestone. The tomb also contained six storerooms distributed in the superstructure of the tomb.

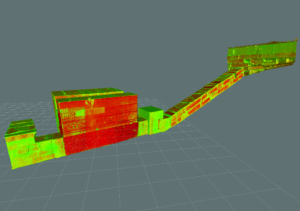

Fig. 7. 3D model of the tomb of Khuwy. Photo: V. Brůna

Like in the tomb of Khuwy, the substructure of Isesiankh’s tomb was reached through a descending corridor, which starts in the north-east corner of the pillared hall. The corridor lead to a vestibule and a large burial chamber with a huge white limestone sarcophagus placed in a western recess. A large storeroom was situated to the south of the burial chamber, with its walls and ceiling blocks still preserved. No decoration was found in Isesiankh’s burial chamber.

Fig. 8. View from the south of the tomb of Isesiankh MSE3. Photo: P. Košárek

The two tombs of Khuwy and Isesiankh prove the importance of Djedkare’s royal cemetery and its exploration. They provided us with a large amount of new information concerning the transformation of funerary beliefs during Djedkare’s reign and the transitional period between the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties