- Era4th dynasty

- Project DirectorMark Lehner

- LocationGiza

- AffiliationAncient Egypt Research Associates

- Project SponsorAntiquities Endowment Fund

- Project Dates2016-2018

When Mark Lehner first began scaling the most famous statue on earth in 1979, he may not have realized how long it would take to make the results of his work available to the public. But Lehner and an ARCE-funded team did indeed climb, map and measure the Great Sphinx, with the records of that long-hidden effort now available online to the world.

On January 15, 2018, an expanded digital version of the decades-old ARCE Sphinx Mapping Project Archive was released and shared for the first time the intricate maps, rough notes, precise measures and resulting revelations from Lehner and the rest of his team. This online release came 35 years after the end of the ARCE project and 4,500 years or so since the Great Sphinx was carved from the same bedrock used for the Giza Pyramids.

The goal of the mapping was to understand the origin and preservation of the Sphinx from careful, recorded observations of its structure and geology. The idea was to read history from the condition of the man-lion’s core and its various masonry skins, from a 1:50 scale survey of this stratified narrative and even from tool marks and mortar.

For various reasons, Lehner’s 1991 Ph.D. dissertation at Yale – the documentary interpretation of what was found in 1979-83 – lay unpublished and available only in a substandard paper copy. The actual maps, drawings, photos, notes and records behind that dissertation went into storage. But no longer. The ARCE Sphinx Mapping Project Archive is the world’s first online dataset to document the history of masonry work on the Sphinx.

Lehner is now the energetic, well-known president of the Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA), a multidisciplinary organization that focuses on the Giza plateau. In 1978, before he became one of the world’s most recognizable Egyptologists, Lehner had just helped excavate the northeastern corner of the Sphinx sanctuary under the direction of Zahi Hawass, then the chief inspector of the Giza Pyramids.

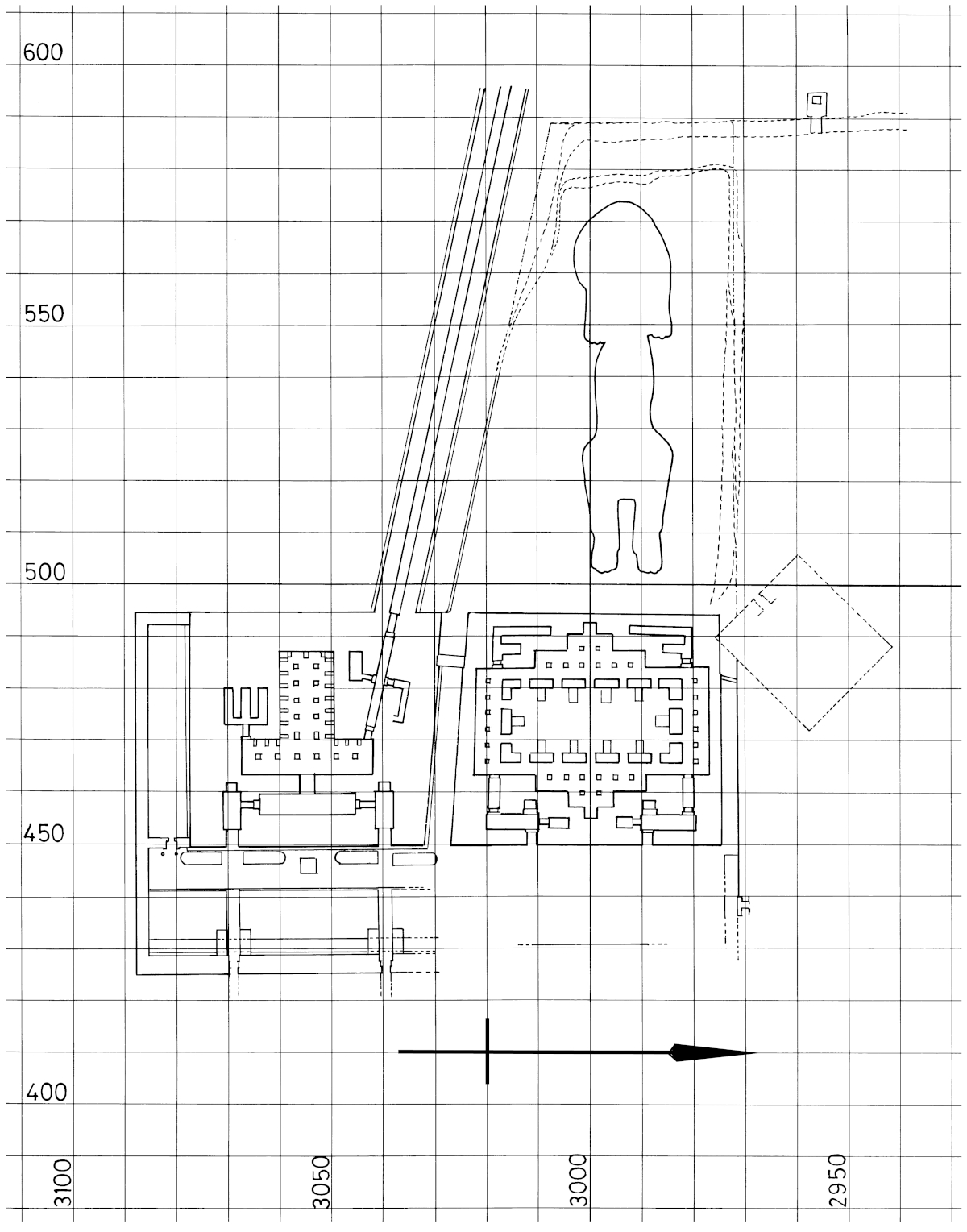

In 1979, Lehner approached Paul Walker and James Allen – then the two leaders of ARCE – about his idea to map the famed statue. Together, they conceived the Sphinx project to produce the scale plans and elevations of the Sphinx itself and to map the greater Sphinx site, including three nearby temples and the larger quarry forming the greater Sphinx “amphitheater.”

With funding from The Edgar Cayce Foundation and with Allen (now the Wilbour Professor of Egyptology at Brown University) as principal investigator, the Egyptian government gave its permission. Lehner became field director, with he and Allen enlisting surveyors, archaeologists, geologists and other Egyptologists, not to mention staff, workers and others. The École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris furnished the ARCE project with field notes, plans and 226 photographs compiled by Pierre Lacau from excavations of the Sphinx by Emile Baraize between 1925 and 1936.

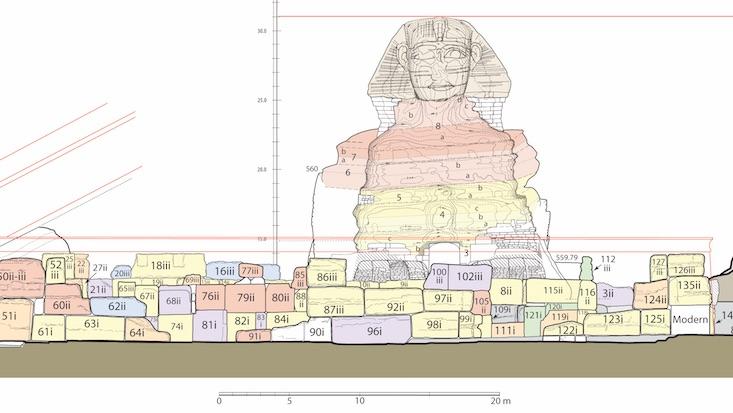

The mapping began with a grid system starting from a spot near a front toe of the lion’s right paw. First, surveyor Ulrich Kapp used a barbell-shaped, dual Jena-Optic stereo-metric camera to take photographs in stereo pairs. To complement Kapp’s photogrammetric elevations, the next job was the actual 1:50 master plan of the whole Sphinx. Without the benefit of today’s technologies and drones, Lehner and his team slowly completed the arduous task of recording, by hand, the details of a statue three-quarters of a football field long and more than 66 feet (20 meters) tall. The technique was offset planning, also known as baseline offset survey, then a common method for scale line drawings of ancient surfaces. Today, it’s all electronic and digital, but back then, the tools were string, bobs and pencil on paper.

When Emile Baraize excavated the Sphinx in the early 20th century, he found masonry skins of three ancient periods. Lehner found that these various skins formed convenient ledges to map around the Sphinx core body. After this challenging process, Lehner and team moved to the rest of the giant beast. For the head, Lehner triangulated 63 points on the face and headdress from grid points on the floor.

To some extent, the monument’s deterioration over tens of centuries became an opportunity to expose secrets buried by time. This was never as clear as in October 1981, when a patch of veneer from an ancient skin and the 1926 repairs collapsed from the north hind paw and spawned a six-year effort at repair and restoration. Lehner was able to map and photograph the exposed insides of the lion during those repairs. Later, after a chunk of Sphinx shoulder fell in February 1988, a new series of repairs was performed, guided, in part, by the ARCE mapping.

After he finished mapping the Sphinx, Lehner went stone-by-stone to map at 1:100 the Sphinx Temple in front of the lion’s paws and the adjacent Khafre Valley Temple. This temple mapping and the team’s intensive study of the geology of the stones revealed how builders and quarrymen made the Sphinx and the two temples as part of a massive quarry-construction landscape project.

As if to match the colossal scale of the Sphinx itself, Lehner’s mapping was grand, too: Even at 1:100, half the scale of the master drawing of the Sphinx statue, the combined map of the Sphinx, Sphinx Temple and Khafre Valley Temple, plus a schematic plan of the Amenhotep II Temple, measures 4 by 6 feet (1.23 by 1.83 meters). These maps and plans added impressively to Lehner’s dissertation and to the many documents, notes, measurements and photos that supported it.

In May 2016, Lehner’s AERA received an Antiquities Endowment Fund grant from ARCE. The goal, finally, was the conservation and online publication of the archive of the 1979-83 Sphinx Project led by Allen and Lehner. Lehner and AERA team members organized, scanned, contextualized, described and preserved 364 maps and drawings, 3,857 slides, 1,740 black-and-white photographs and reports, journals and survey data. Partnering with Eric Kansa and Open Context – a web-based publishing service that archives archaeological research data for preservation and public access – the team created a dynamic, permanent online home for the ARCE Sphinx Mapping Project Archive.