- EraMiddle to New Kingdom

- Project DirectorProject director of the Senwosret III excavation: Adela Oppenheim l Graffiti Project Principal Investigator: Hana Navratilova

- LocationDahshur

- AffiliationUniversity of OxfordThe Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Project SponsorAntiquities Endowment Fund

- Project dates August 2022 - July 2023

Written by: Hana Navratilova

The necropolis at Dahshur hosts intriguing evidence of ancient Egyptian life and culture, ranging from Old Kingdom pyramids and settlements to Middle Kingdom pyramids to New Kingdom tombs to simple burials from long periods of Egyptian history. The site’s entire life is more captivating than any individual monument. Equally, no building is finished and frozen in time. The ongoing exploration of the Middle Kingdom pyramid complex of Senwosret III at Dahshur has revealed that the pyramid precinct was both revered and exploited by generations of users, from devoted visitors to workmen involved in dismantling the pyramid complex. Research into New Kingdom inscriptions and contemporary and later artefacts gives a fuller picture of the life – and the demise – of the structures that once surrounded the pyramid of Senwosret III.

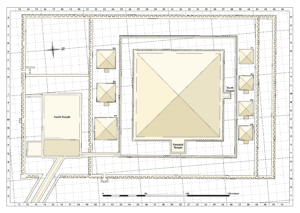

Fig. 1 Plan of the pyramid complex of Senwosret III, drawing Sara Chen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The project introduces a ‘pyramid complex biography’: how a monumental group of buildings live and die. This perspective is important for the contemporary person approaching the complex, who may focus on the ideal image of an ancient monument, without realising how it might have been peopled, used and perceived in antiquity, the ways in which it changed, and its interaction with its surrounding environment.

Fig. 2 Monuments in context: the north side of the pyramid of Senwosret III with the Red Pyramid of Snefru in the background, photo Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Secondary inscriptions (or graffiti) in the Senwosret III complex were first noted in the 1830s by the John Shae Perring and Howard Vyse mission, and recorded in the 1890s by Jacques de Morgan. They have been studied systematically from 1990 on by the Egyptian Expedition of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, headed by Adela Oppenheim and Dieter Arnold. The epigraphic research is ongoing and reveals the New Kingdom life of a Middle Kingdom pyramid precinct. An Antiquities Endowment Fund grant has supported continued graffiti research and preparation of the publication of the first volume of secondary epigraphy from the Senwosret III precinct: the texts and figures from the Pyramid Temple and the North Chapel, the excavation of which is largely complete. The work in the South Temple, probably one of the largest temple buildings in Egypt before the New Kingdom, is ongoing.

Fig. 3 The destruction layers in the South Temple of Senwosret III, photo Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The fragile texts and figures, added in ink or by incisions, tell many stories. Since the 1950s, we use the concept of ‘visitors’ inscriptions.’ These texts are mostly from the New Kingdom and refer to ancient visitors, who entered tombs and temples, wrote down their names, often along with those of an ancient king, and explained that they were there to admire the monument and make offerings to the long-deceased sovereign. Yet, as the pyramid precincts from Abusir to Dahshur have revealed, that was not the only interest New Kingdom Egyptians had in the monuments. In the Ramesside Period, the buildings, made of fine limestone, were dismantled and the stone re-used. Notes appeared, marking stone blocks for delivery at contemporary building sites.

Fig. 4 H. Navratilova documenting graffiti on column fragments in spring 2023, photo Richard Lee © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Increasingly, the interest in pyramid precincts has expanded. In addition to the fascinating architecture, reliefs and texts, we also look at the communities of people who were involved in the life and death of a pyramid. Thanks to finds in Giza, as well as Abusir, and Lahun, the builders are now much better known, as are the priests and workers who maintained and served the royal complexes. But the later users, curious visitors, pilgrims even, and ultimately the demolition crews, have been more enigmatic.

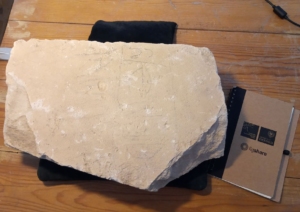

Fig. 5 One scribe obliterated the name of his predecessor. The traces of the second line still preserve the name of Senwosret III. A fragment from the Pyramid Temple, photo Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The evidence at Dahshur makes them visible: some had training as craftsmen, others demonstrated their literate skills by quoting Kemyt, the training and instruction text originally from the Middle Kingdom, still others venerated Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom. They took the spaces of a royal funerary monument to be their own, and their names, prayers, and concerns were added to the ancient rooms. On occasion, they competed and even obliterated the names of those who had written earlier graffiti. On one fragment from the Pyramid Temple, someone took care to delete the name of a previous writer, while preserving the royal name of Senwosret III (his throne name Khakaura).

The finds from the precinct of Senwosret III offer a unique collection of texts and images that capture the voices of the early admirers of the pyramids, as well as of those who were given the task of recycling the stone. Each of the temples or chapels within the pyramid complex has its own reception history.

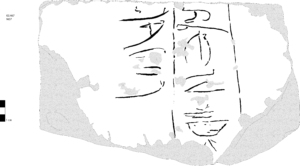

Fig. 6 Checking a fragment from the North Chapel, carrying the introductory formula from Kemyt, photo Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 The finished line drawing of the Kemyt text, Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Reconstructing this history in a demolished pyramid complex is a demanding task. The walls of Senwosret III’s temples and chapels are broken into hundreds of thousands of pieces, with tens of thousands preserving portions of relief decoration; however, most of the wall decoration is lost. The fragments preserve traces of later texts, often damaged, and almost always incomplete. With the exception of a few better preserved, longer examples, the texts have to be reconstructed, using parallels from other sites. They also have to be recontextualised where possible with the original spaces and sections of wall decoration. The epigrapher works in close cooperation with colleagues studying Middle Kingdom reliefs and architecture, to recreate the spaces and experience of the New Kingdom visitors and ‘de-constructors.’

The texts and images are traced, digitised and photographed. Excavation of Senwosret III’s Pyramid Temple and the North Chapel are now largely complete, and publication of their graffiti is ready. Further investigation will help to put the secondary epigraphy in context with other post-Middle Kingdom finds.

Fig. 8 The ongoing work in the South Temple, photo Hana Navratilova © The Metropolitan Museum of Art