- EraPharaonic

- Project DirectorDr. Mark Lehner and Dr. Zahi Hawass

- LocationGiza Plateau

- AffiliationAERA (Ancient Egypt Research Associates)

- Project SponsorAntiquities Endowment Fund

- Project Dates2019-2020

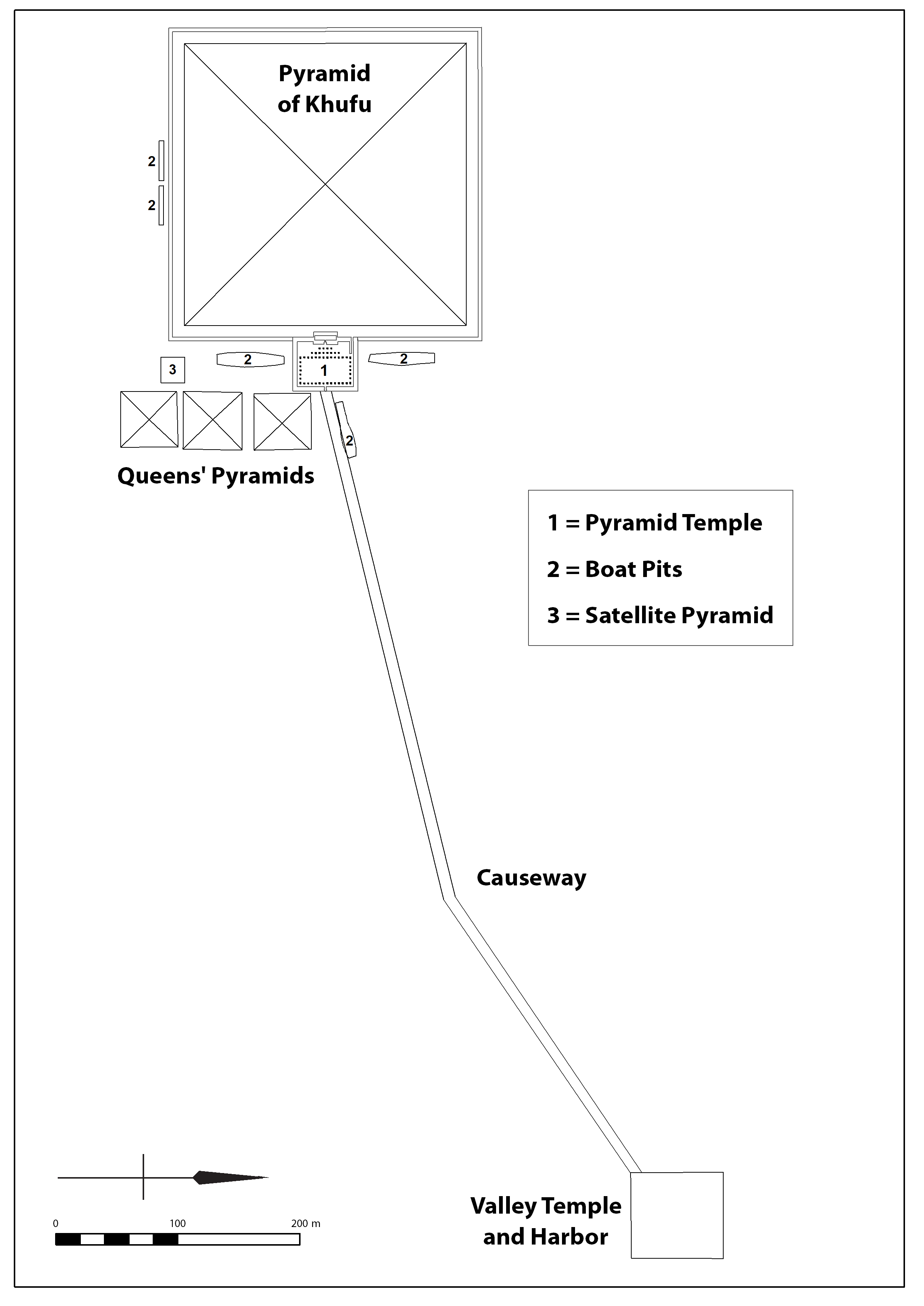

The Great Pyramid of Khufu is the largest pyramid ever built and one of the most popular tourist sites in the world. But few of its visitors ever knew a grand pyramid temple once rose on the east side of the pyramid. Nor did they realize, as they walked or rode horses and camels, that they were helping obliterate the scant remains of the temple, the central focus of the Great Pyramid Complex. The complex included a causeway, another temple, queen’s pyramids, and more.

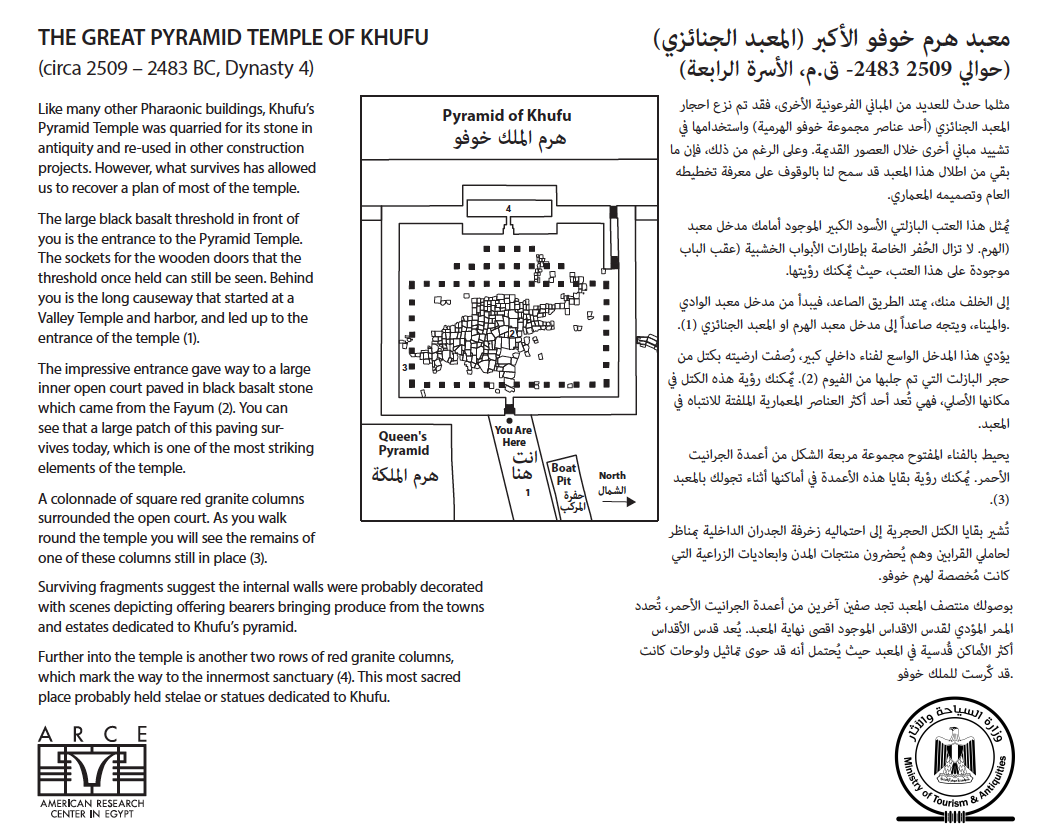

Schematic plan of the Great Pyramid complex.

Since 1995, when the Ministry of Antiquities removed an asphalt road that covered much of the temple remains, it has still endured an onslaught of traffic every day—visitors, souvenir sellers, camels, horses, and horse-drawn buggies. The site became a parking lot for camels and horses.

Archaeologists Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass knew something had to be done to save what remained of the temple. They also believed that the visitor’s experience could be far more compelling and enriching if they could learn about the temple. So Lehner and Hawass launched the Great Pyramid Temple Project (GPTP) to conserve the pyramid temple and present it to visitors.

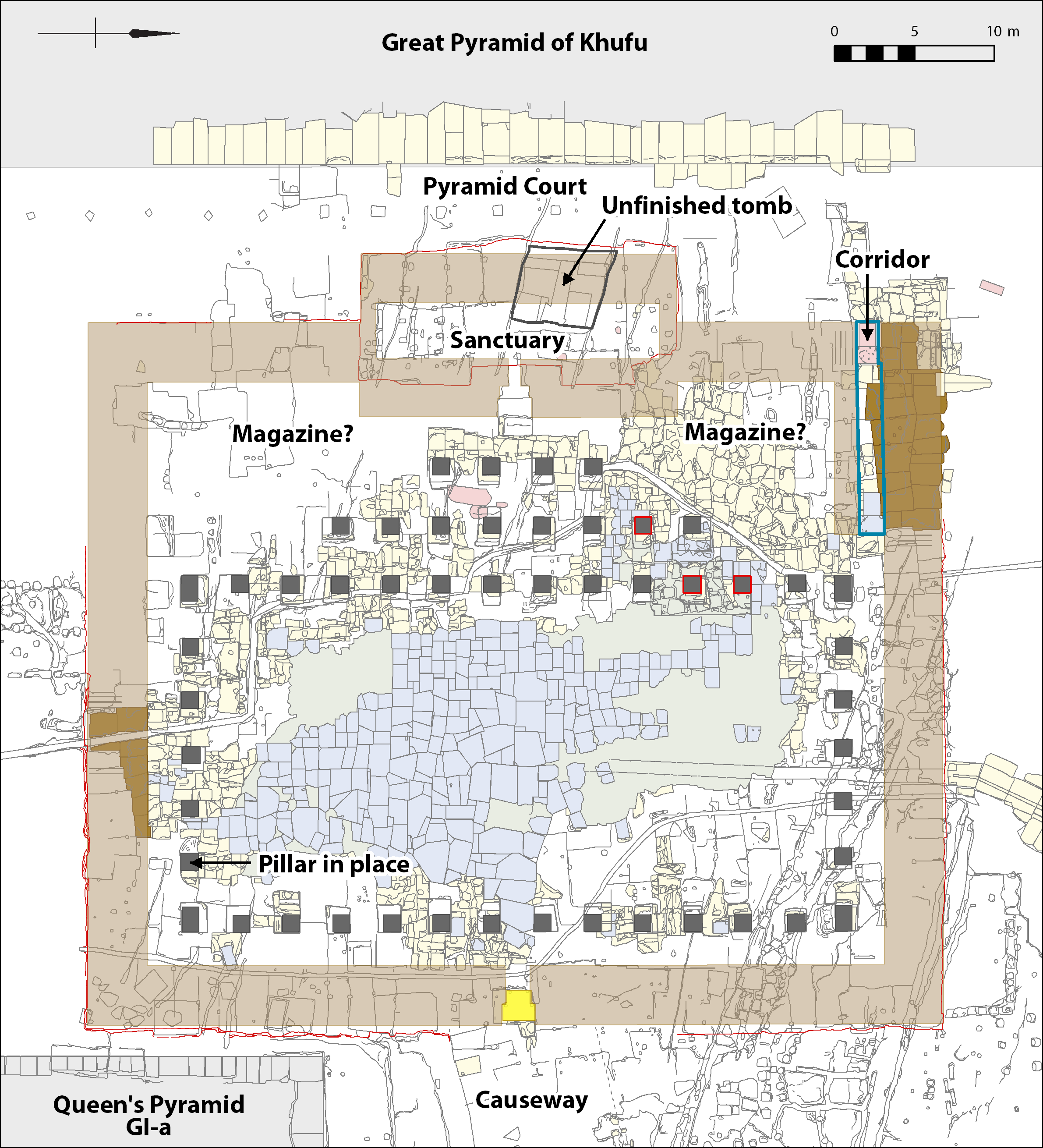

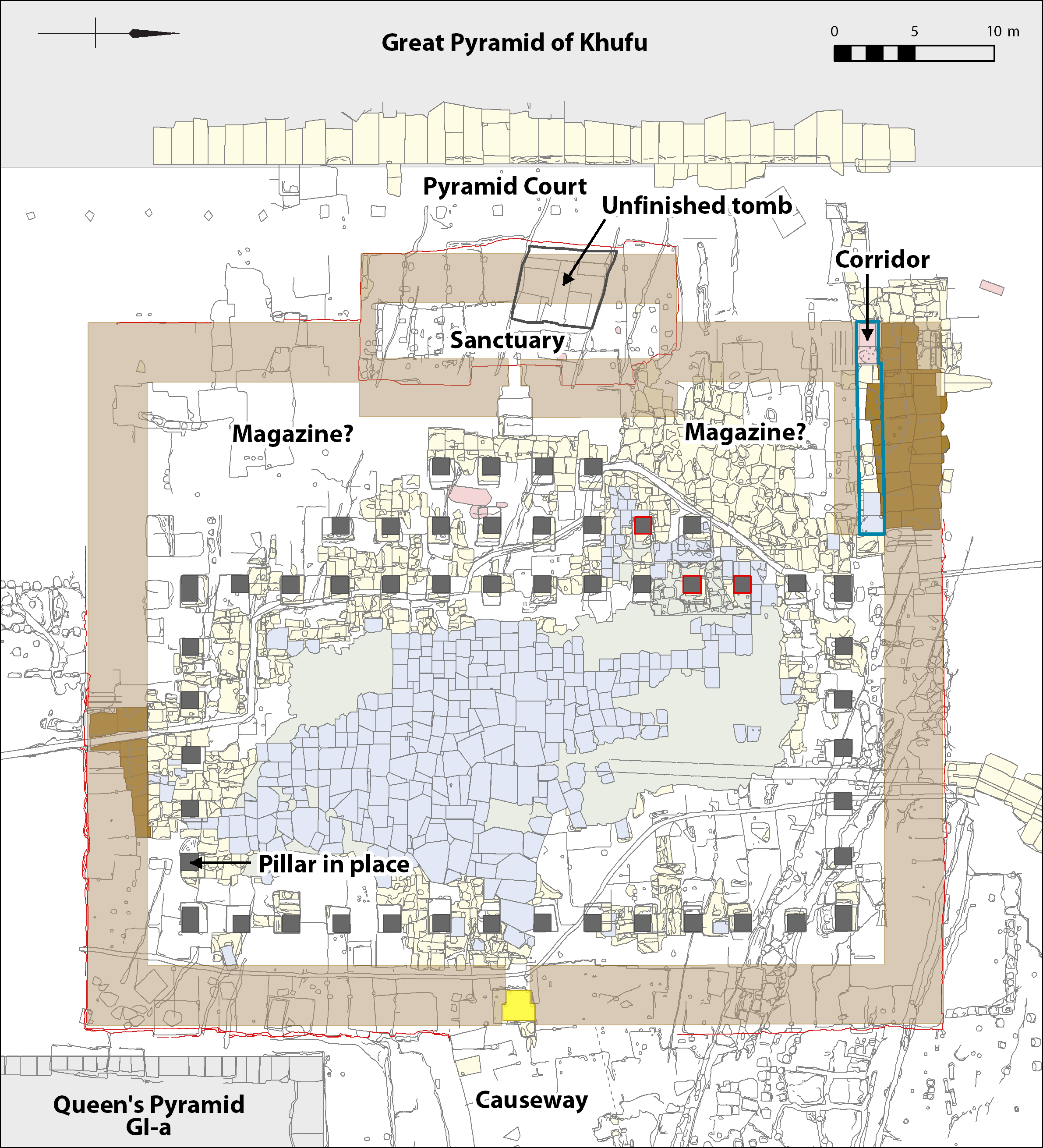

Supported by ARCE’s Antiquities Endowment Fund, the GPTP team began work in September 2020. The first task was to comprehensively document the remains. They assigned a number to every physical feature left by an archaeological process or event, such as a hole cut into the bedrock, and then documented each feature. They positioned the features on a map and photographed and described them. All visible archaeological features were recorded: those reflecting the initial layout and construction of the building, some predating the temple, and others dating much later, such as blocks displaced when it was dismantled. Recording all archaeological remains was crucial to understanding the sequence of events at the site of the temple as a whole.

The great pyramid temple site showing all the features recorded and our proposed reconstruction (light brown) of the temple walls. Dark pink indicates limestone pavement laid down as foundation for the outer wall.

Once they documented the site, Lehner, Hawass, and team had a comprehensive record of what remained. Now they could work out the history of the pyramid complex: how Khufu’s builders conceived and constructed the complex. Here is their vision of the temple as it may have looked in its heyday:

The great pyramid temple site showing all the features recorded and our proposed reconstruction (light brown) of the temple walls. Dark pink indicates limestone pavement laid down as foundation for the outer wall.

A long causeway ran from Khufu’s valley temple up to the black basalt threshold at the pyramid temple entrance. Here a double door would swing open to a court with sunlight blazing down on a burnished floor of black basalt slabs. Rising high up behind the temple, the polished white casing of the Great Pyramid glistened. If the causeway had been roofed and poorly lit, the effect on entering the open court would have been startling, dazzling, blinding—a gigantic special-effect wrought in stone.

Huge red granite pillars lined the sides of the court, a massive presence altogether: 50 pillars, 3.5 feet (2 cubits in ancient Egyptian units) square except for the four slightly larger pillars at the corners. Scenes depicting Khufu’s 30-year jubilee celebration probably ran across the walls; the GPTP team found limestone fragments with snatches of such scenes buried in temple debris. In the northwest corner, a narrow corridor ran along the north wall and opened into the court encircling the Great Pyramid.

On the west side of the temple, the walls receded into a stepped bay populated with two rows of the pillars, flanking a narrow passageway down into the inner sanctuary. Statues of the king might have stood against the back wall of the bay, gazing out to the east through the spaces between the pillars, illuminated only by light from the court or from slits at the tops of the walls. The effect would have been dramatic: the statues seen in the liminal zone between dark and light, emerging from the Netherworld.

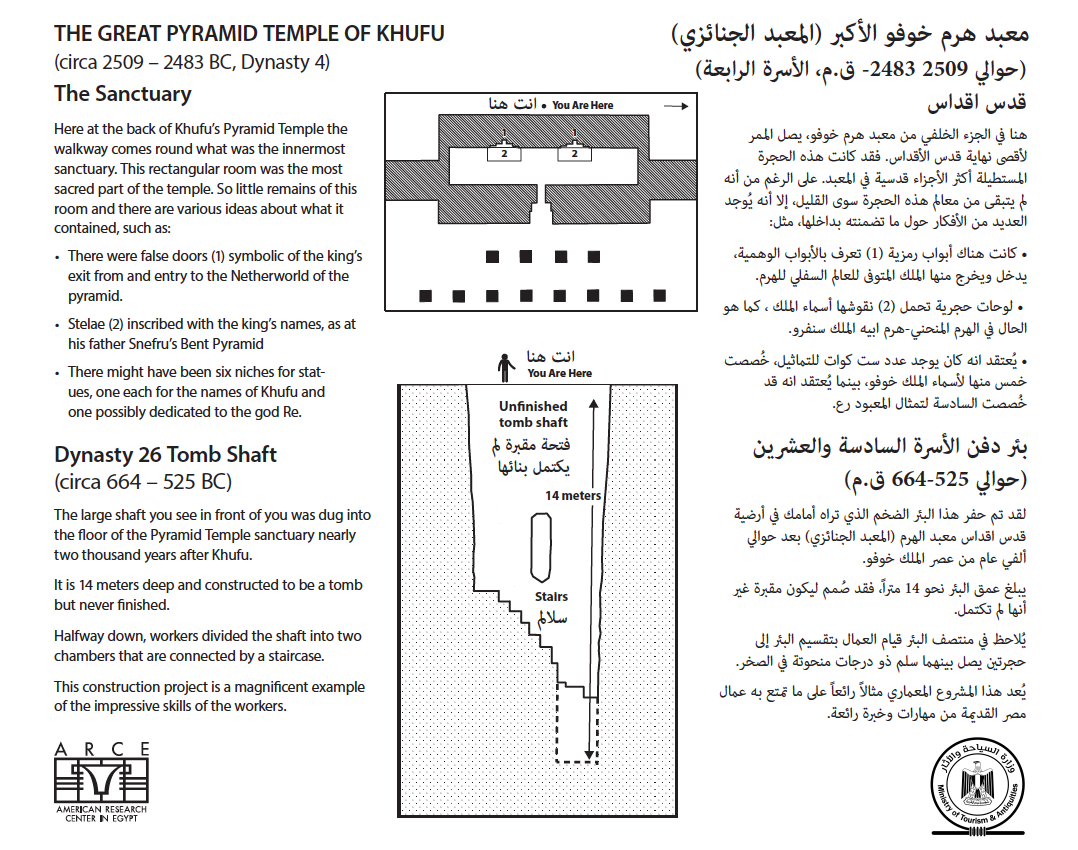

In the inner sanctuary, where little remains today, statues might have stood in niches, or a “false door” may have allowed the dead king to emerge from his tomb to receive offerings. But the only remaining trace of the sanctuary is a cut into the bedrock, a sunken foundation, which was partially destroyed by a 46-foot-deep (unfinished) tomb shaft in the center, probably dug 2,000 years after Khufu’s time.

How was this temple built? Khufu’s workers first prepared a level surface for the temple wall by pounding out a foundation in the limestone bedrock. Next they turned to the interior and cut sockets into the bedrock for the 50 pillars and the thresholds. The sockets were not all of the same depth, apparently cut to accommodate pillars of varying lengths, so that they would stand at the same height to support the roof. For the floor, workers prepared an under layer of limestone pieces arranged and cut to conform to the angular bottoms of the basalt floor slabs in order to achieve a level surface. They chose to work the soft limestone rather than the irregular basalt slabs, because basalt is extremely hard. And they pieced the irregular slabs together like a jigsaw puzzle rather than cut them into standard shapes. Once the floor was installed, the builders moved on to the outer walls and to the roofed areas of the temple.

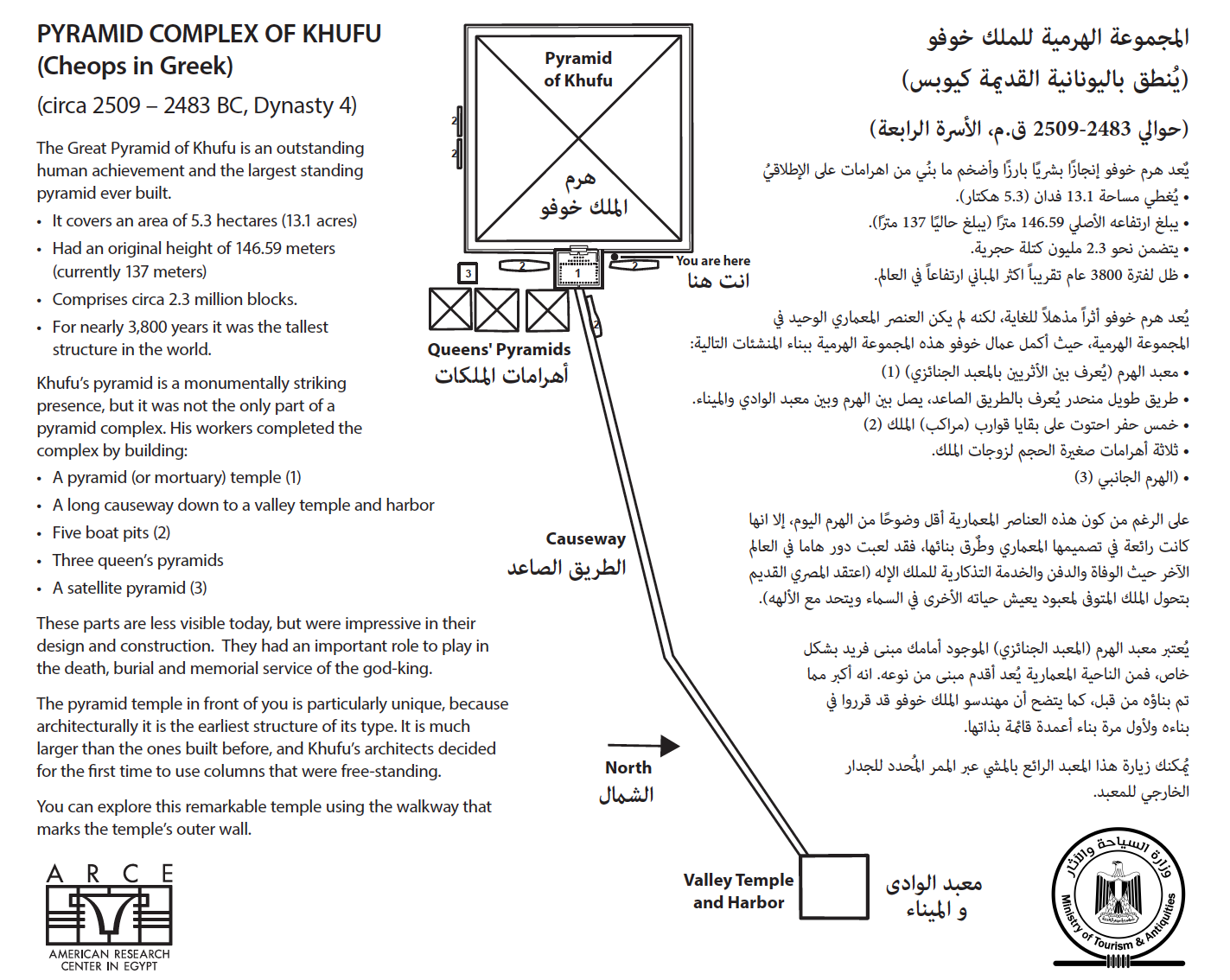

The GPTP completed the work at the temple by installing a controlled access walkway around the outer wall line of the temple. The walkway is open to the temple; no fencing was needed to keep visitors out as they chose to stay on the walkway rather than tread across the irregular surface of the temple remains.

Khufu’s pyramid temple walkway in the first light of day.

To compliment the walkway and improve visitor experience the GPTP team installed three large information panels around the temple. One explains the layout of Khufu’s pyramid complex, the second is about the pyramid temple itself, and the third about the sanctuary and unfinished tomb shaft.

Pyramid Complex of Khufu ( Cheops in Greek).

The Great Pyramid Temple of Khufu.

The Great Pyramid Temple of Khufu.

The GPTP preserves Khufu’s remarkable temple for future visitors and scholars and offers the visitor a meaningful, compelling experience of Khufu’s magnificent pyramid complex as a whole.