- Era18th dynasty

- Project DirectorLyla Pinch-Brock

- LocationLuxor

- AffiliationAmerican Research Center in Egypt (ARCE)

- Project SponsorUSAID

- Project Dates2002-2003

Situated at the highest point of the West Bank’s royal necropolis hill in Luxor, the tomb of Anen belonged to an ancient Egyptian priest who served under the reign of Amenhotep III. Time and neglect left the tomb damaged and full of rubble until ARCE took on a project to restore and open it to the public in the early 2000s.

Anen probably served in the military before joining the priesthood, and earned a number of honorable titles, including Guardian of the Palanquin, Second of the Four Prophets of Amun and Greatest of Seers. Beyond his high spiritual standing, Anen also came from a notable regal line. The brother of Queen Tiye, Anen was the brother-in-law of Amenhotep III, a maternal uncle to Akhenaten and a maternal great-uncle to Tutankhamun.

The specific significance and scholarly value of Anen’s tomb made it a good candidate for an intensive restoration project backed by ARCE and directed by archaeologist Lyla Pinch-Brock. The effort focused on the deterioration of the tomb’s colorful wall paintings, as well as overall structural integrity, and has made the tomb accessible to scholars and visitors alike for the first time.

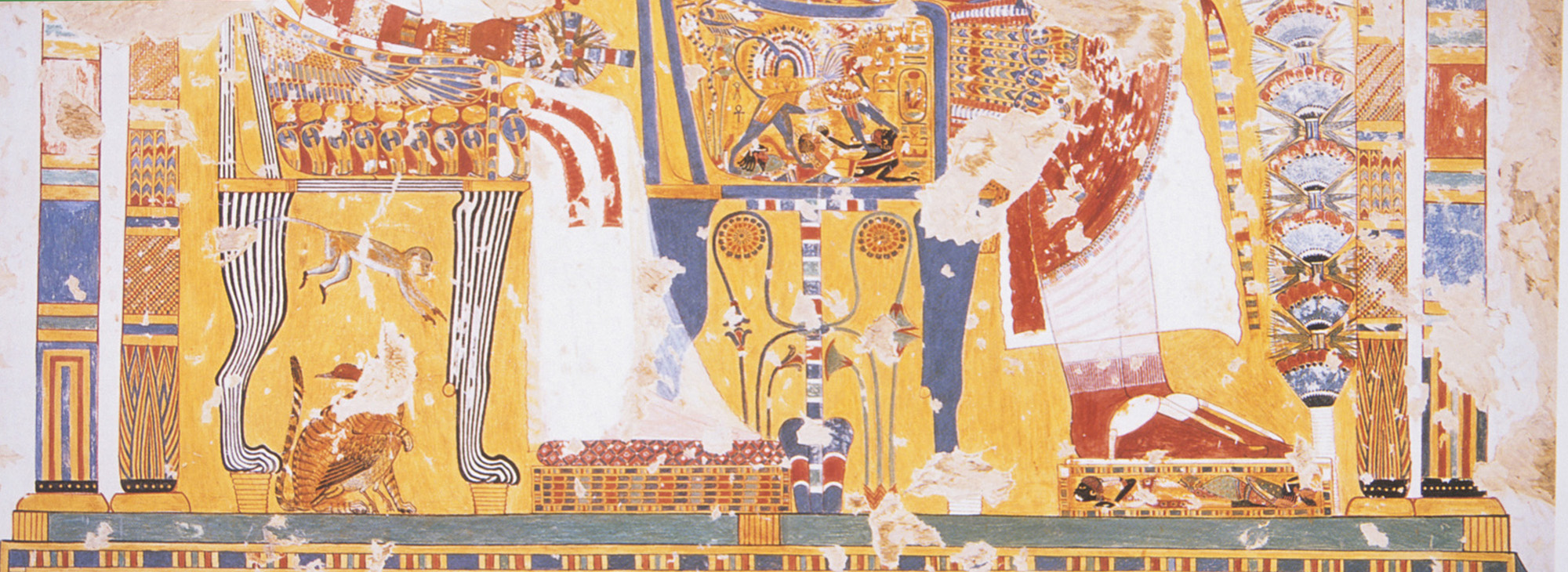

Composed of a main hall and an inner burial chamber, the T-shaped layout of Anen’s tomb is typical of the 18th dynasty. Two primary wall reliefs depict a series of powerful images, including rekhyt birds, a hieroglyph with flapping wings raised in adoration. This symbolic image was unique to the New Kingdom period and represents bound captives or the captured enemies of Egypt. A second exquisitely detailed image shows Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye receiving tribute from foreign visitors. The bowing figures beneath the thrones represent the Nine Bows, or the leaders of the foreign dynasties dominated by Egypt at the time: Minoa, Babylonia, Libya, Bedouin, Mitanni (the Assyrians), Kush, Irem (Upper Nubia), Iuntiu-seti (Nubian nomads) and Mentu-nu-setet (coastal Levant). The relief is teeming with movement and symbolism: a cat holds a duck by the neck beneath the throne of Queen Tiye and a leaping monkey and foreign enemies lay on King Amenhotep III’s foot cushion, crushed under the weight of the pharaoh’s feet.

At some point in the tomb’s history, the roof collapsed and filled the chambers with rubble. Exposure to extreme light and heat, as well as infrequent but intense flooding, left the wall reliefs badly deteriorated. In addition, looters cut sections of the reliefs from the walls and discarded fragments in the tomb, and chiseled the faces from the principal painting of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye.

The project conservator, Ewa Parandowska, first worked on the rekhyt relief. She relied on repetitive imagery to repair the mission sections and re-adhered fragments with special mortar. The team stabilized and reinforced the wall, and mechanically cleaned the relief with brushes and scalpels.

Conservation of the relief of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye was more challenging. The relief is featured in a painting by Nina de Garis Davies recorded for an expedition of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1929 and still on display at the museum today. Parandowska used the painting as a guideline to restore the damaged or chiseled sections of the relief. These reproductions are differentiated easily from the original painting and mimic an ancient painting technique where craftsmen sketched the relief images in red ink before filling them with color.

As a final precaution, the team constructed a protective display box over the two restored wall reliefs to protect them from human or environmental damage and built a series of low slanted walls along the top edges of the tomb to divert rainwater. From a conservation perspective, these less invasive solutions are preferable to installing an entirely new roof in the tomb, which would have altered substantially the appearance and materials of its original walls and floor.

Speaking on the success of the restoration, project director Pinch-Brock explained that the tomb of Anen is a “good example of what can be done to restore a tomb apparently beyond help. ARCE conservation projects such as this one can open up otherwise inaccessible tombs to scholars, and further our knowledge of Egyptian history.”