- EraMiddle Kingdom

- Project DirectorKate Liszka, Meredith Brand , and Bryan Kraemer

- LocationWadi el-Hudi and Dihmit South

- AffiliationCalifornia State University San Bernardino

- Project SponsorResearch Supporting Member Field Work Grant from ARCE

- Project Dates2024-2025

Written by Kate Liszka, Bryan Kraemer, Amy Wilson, and Ariel Singer

In 2015, on the first day of the season while we were setting up the mapping grid for the first time at Wadi el-Hudi, Bryan Kraemer (co-director, chief surveyor, and chief epigrapher) climbed up a small rocky outcrop south of Site 9 with the intention of setting up a mapping control point. But when he was there, he looked down to discover that he had not been the first person to make a mark on this outcrop. Officials from the Middle Kingdom had been there centuries previously and used the promontory to erect stelae, which over the years had fallen over. This discovery at the newly named Site 15 changed our understanding of the chronology of Site 9 and our knowledge of viziers and expeditions in the Middle Kingdom, and it was the catalyst for Bryan Kraemer and Ariel Singer to create a new method of digital epigraphy to document uneven, carved inscriptions in three-dimensions.

Bryan Kraemer and the discovery of WH203 at Site 15

This first-day discovery was a happy preview of things to come. Since that time, almost every team member of the Wadi el-Hudi Expedition has discovered previously unknown inscriptions at Wadi el-Hudi and Dihmit-South, even the ceramicists who were not looking for them. Every new inscription, however, presents new technical problems: they are often carved on local stones found in the desert. Thus, they are uneven, having never been prepared as smooth flat-sided stelae by craftsmen. Traditional epigraphy techniques often assume a flat surface. But recording these inscriptions as if they were on flat surfaces could introduce inaccuracies into the drawings. Also it would not help to elucidate how the inscriptions are nested into the landscape, often being situated for some discoverable reason at the place and on the uneven rock surfaces on which they are found.

Several digital technologies have been developed over the last ten years for the use of archaeologists and Egyptologists in their work recording Egypt’s monuments, especially some that involve recording in 3D. We were thrilled to receive a Research Supporting Member Fieldwork Grant from ARCE in 2024-2025 to record and translate fourteen historically important stelae found since 2015. This was done digitally with an aim to produce 3D renderings, while also discovering the inscriptions’ larger purposes within the landscapes of Wadi el-Hudi and Dihmit South. The three stelae found in 2015 on Site 15 present particular problems that these recording techniques might help to address because they are highly faded, having been damaged by direct sun, wind, and rain exposure for 4000 years.

Ariel Singer checking epigraphic drawings on WH22+23

We have examined each stela using multiple new technologies, including Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), D-Stretch, and meticulous photography to show details. We have made a 3D model of each stela using photogrammetry and then over this model or on an orthophoto produced from it (a photo corrected for uniform scale and geographic position), we have been able to do epigraphic drawings of the inscriptions, thereby preserving the natural curves of the rocks. At every stage, multiple Egyptologists collaborated together to examine both the details of the drawing and the transliteration/translation of the text to elucidate as much of its meaning as possible. Moreover, the Wadi el-Hudi team has also been building a larger virtual 3D landscape of the entire archeological site that will be accessible for anyone to visit digitally. Each of these individual 3D models of artifacts could also be inserted into the larger virtual landscape in order to reconstruct what the landscape was like 4000 years ago. This reincorporation of the monument in its original landscape, digitally, will help to decipher it and communicate to a wider audience what its meaning might have been as a nested part of that landscape.

The three stelae found at Site 15 exemplify the type of historic and social data that can be gleaned from studying these inscriptions in detail. WH201 and WH203 are both dated to year 28 of the reign of Senwosret I. Because Site 15 is only 150 meters south of Site 9 and integrated into its larger landscape, it means that Site 9 must also have been established at least by this reign. Our discovery suggests that Site 9 was not founded later in the Middle Kingdom, as earlier scholars have suggested. Plus, inscriptions from Site 5, a kilometer north, also date to the reign of Senwosret I, further indicating that both amethyst mines at settlements at Sites 5 and 9 were likely used at the same time.

Amy Wilson and Bryan Kraemer mapping the find locations of the stelae on Site 15 with Site 9 in the background

Bryan Kraemer and Michael Kraemer completing RTI photography for WH202

WH201 contains 10 lines of text. Much of the center of the inscription is missing, but a great detail of information can still be discovered. It is an honorary inscription of an unknown official who helped to organize the expedition. The official recorded “bringing the best amethyst,” which must refer to the quality of amethyst discovered in the Site 9 mine. The text also mentions a vizier, whose name is lost, and a sealer named Intef. The sealer and his mother are mentioned again in the last line, implying that he was the dedicator of the stela.Typically, royal expeditions are overseen by the Treasury and officials of the Treasury, but in this case, the expedition for high-quality amethyst seems to have been so important that it was overseen by a vizier himself.

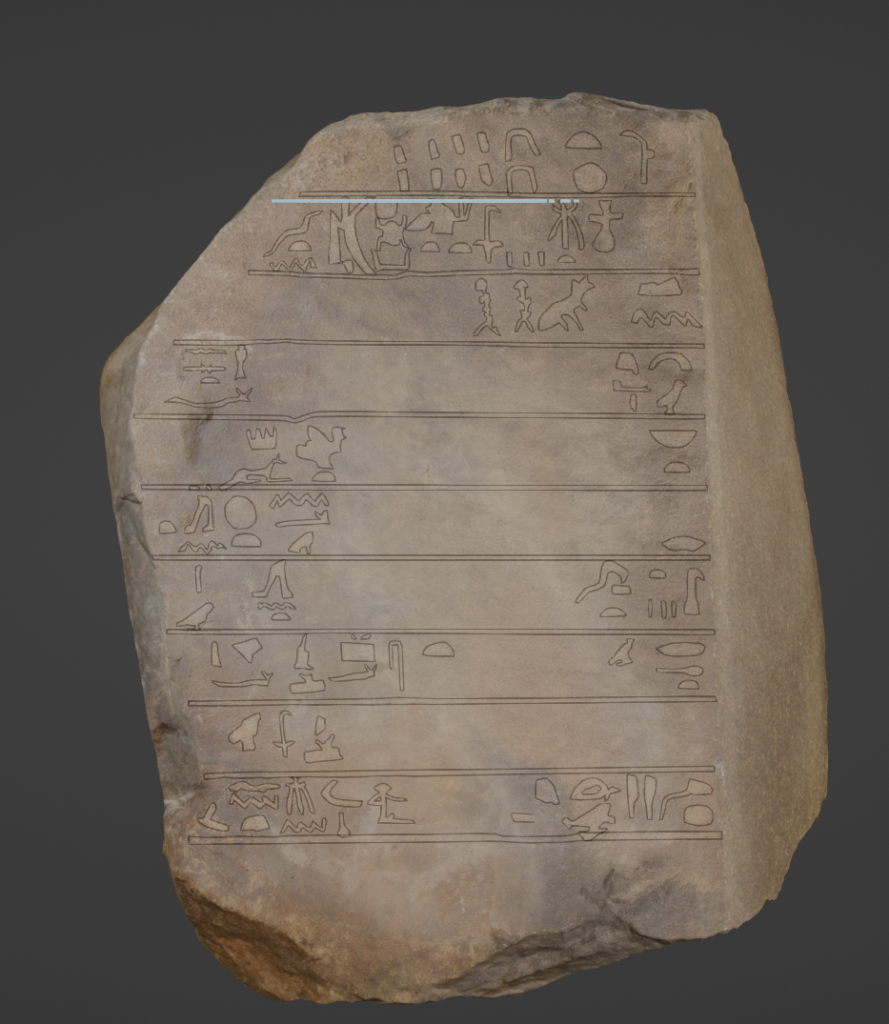

WH201 3D drawing

WH203 contains 10 lines, but line 7 is blank, separating the inscription into two sections. The top half indicates again that a vizier named Intef was likely in charge of the expedition to Wadi el-Hudi. Interestingly, the Vizier Intef is an enigmatic figure who is known to be mentioned only once elsewhere, in stela WH154 dating to year 23(?) in the reign of Senwosret I. As noted by Obsomer (Sésostris Ier,1995: 223), the same Intef possibly was also mentioned onWH7 from Year 20, where he is an Overseer of Works.With further study, we may be able to revive the memory of this faded character of history. The bottom half of WH203 indicates that it was carved by a scribe of the great magistrate named Amenemhat son of Minhotep, who likely oversaw much of the mining activities at Site 9.

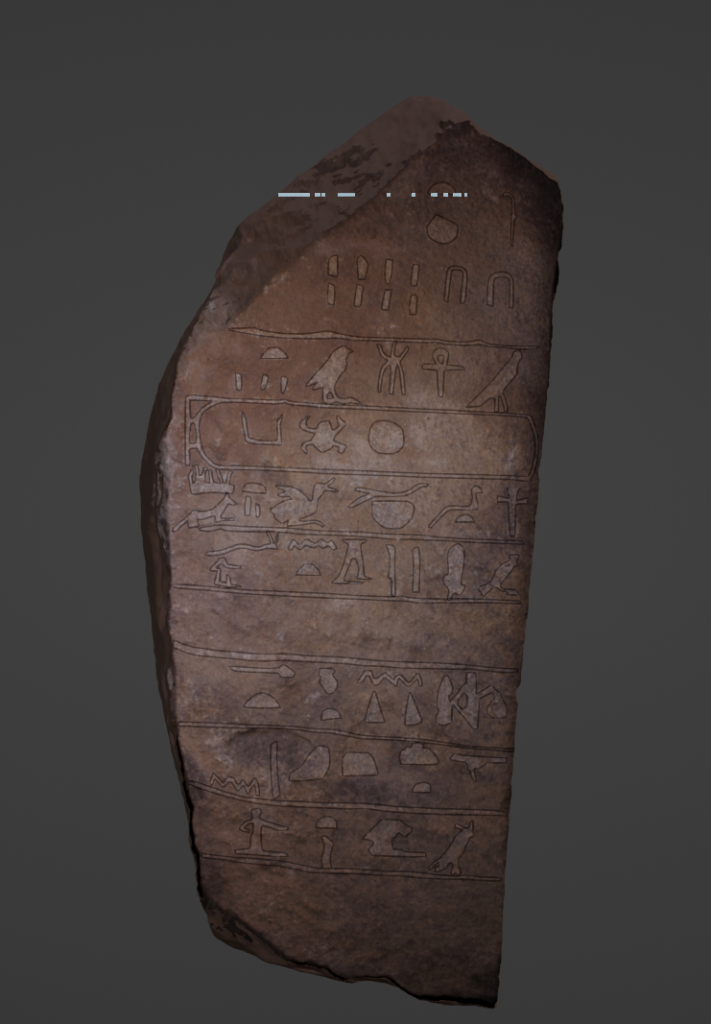

WH203 3D drawing

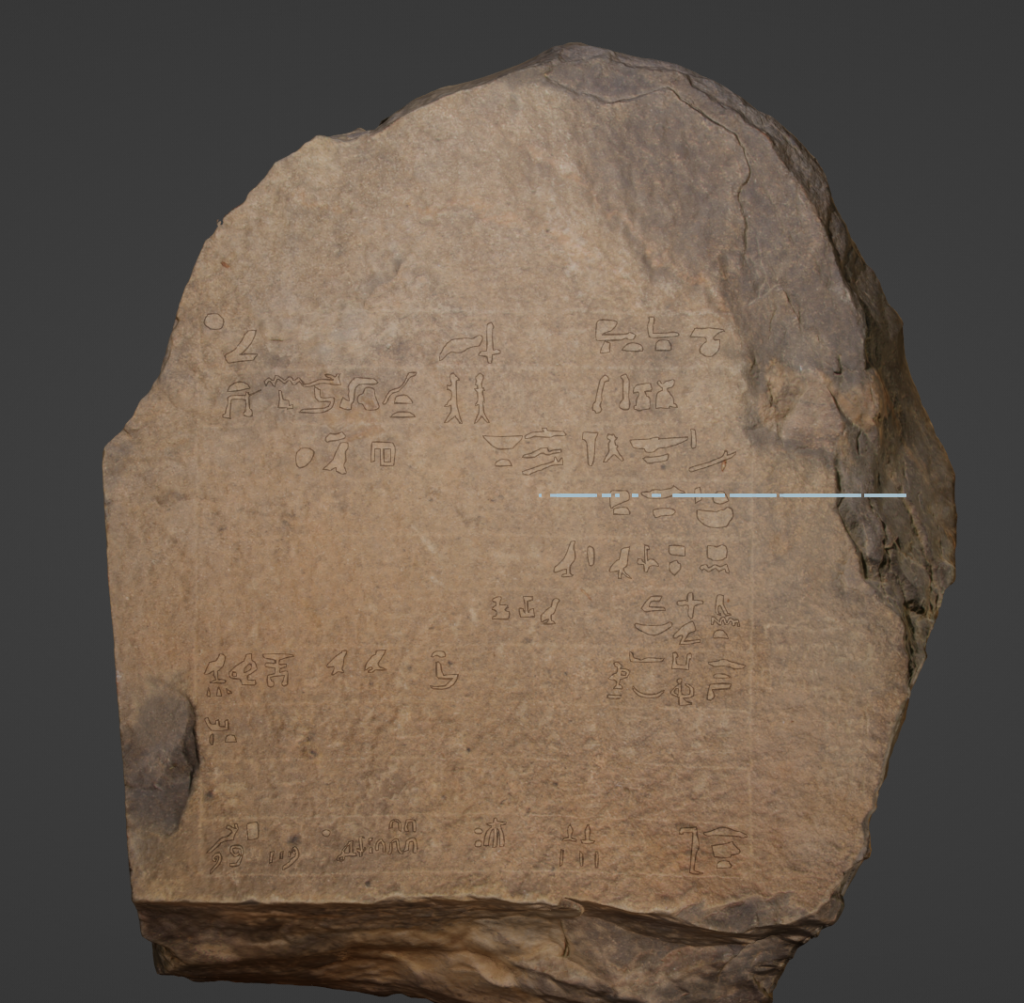

WH202 is extremely difficult to read. Originally the inscription was scratched very shallowly into the surface with small signs that are now mostly faded. However, using these new technologies, individual signs and phrases pop out whose uniqueness and significance tease us. While we will never be able to translate the inscription fully, because too much is lost, it once obviously held an extremely important text detailing the organization of expeditions to Wadi el-Hudi. For example, the inscription starts with a royal titulary inscribed by an unknown official, and ends with an account of the numbers of workers on the expedition. But it leaves our team with more questions than answers.

WH201 3D drawing

We were thrilled to be able to add to the understanding of history and society with new discoveries from Wadi el-Hudi and Dihmit South. Many thanks to the American Research Center in Egypt as well as everyone at the Ministry for Tourism and Antiquities, especially those in the Aswan Inspectorate for supporting our work. Please see our articles in Scribe called “Tales from the Land of Amethyst”and our website for more information and links to publications. You can also follow our activities on social media, via Facebook and Instagram.