The Lost Papers: Rewriting the Narrative of Early Egyptology with the Abydos Temple Paper Archive

In 2013 when Inspector Ayman Damarany reopened a long-sealed chamber in the slaughterhouse area of the Grand Temple of Seti I, he expected to fulfill his assignment to record the decorations on the walls. But he was instead surprised to find the room filled with thousands of documents, many tied up in bundles along the walls and others strewn across the floor.

When he took a closer look, he realized that what he had found was a depository belonging to the Sohag Inspectorate and the broader Egyptian Antiquities Service, with documents – mostly in Arabic – written by employees of the Antiquities Authority from as early as the 1820s. The reams of records included correspondence, excavation reports and survey maps made long before the landscape around the Abydos site took its current form. To organize and preserve the archive, Ayman put together an Egyptian-led international team with members from the Ministry of State for Antiquities, the United States and Europe.

The significance of this trove was quickly recognized for its potential to enhance not only the modern history of one of ancient Egypt’s most revered sites, but also the explorations of locations further afield. More importantly, and for the first time, the early history of Egyptology could be examined from the viewpoint of Egyptians rather than the lens of foreign missions. This archive comprises a unique collection related to the early history of Egyptology, and is currently the only known one of its kind. Before being deposited in the slaughterhouse, these papers, maps and other documents had passed through the hands of the local workers and officials responsible for the management of Abydos and other sites in its vicinity over the recent past. Now, by preserving this precious archive – and eventually making it available to the public – the Abydos Temple Paper Archive aims to provide a more inclusive account of the development of early Egyptology. The project restores the voices of many Egyptian employees of the Antiquities Service who were critical players in bringing to light the history and heritage of ancient Egypt and who are, until now, a long-neglected part of Egypt’s cultural heritage.

The archive project is an Egyptian-American mission under the auspices of the Ministry of State for Antiquities and the University of California, Berkeley, with support from the Antiquities Endowment Fund administered through ARCE and with the permission of the Permanent Committee of Egyptian Antiquities. Our work, over three months in 2017, showed the Abydos archive to be a window into the untold stories of hundreds of Egyptian inspectors, excavators, bureaucrats and guards working for or connected to the Antiquities Service during the formative years of Egyptology.

The range of documents at our disposal, originally prepared or administered by the Egyptian Antiquities Service, are both diverse and distinct: official correspondence between inspectorates, administrations or ministries; unofficial notices or even complaints from ghofora (guards) or employees of the Ministry of Antiquities; and memos with new or updated instructions, especially during times of unrest, hardship or political change. For example, early office ledgers of the inspectorates disclose how Egyptians managed, documented, researched and protected the sites. Some entries record the confiscation of stolen artifacts, trespassing on antiquities land and arguments between ghofora and omda (leader) of a village. The archive also includes diaries of Egyptian inspectors who were excavating or monitoring archaeological sites and official permits to remove sebakh (nutrient-rich soil) from archaeological sites or to sell antiquities (a practice that was legal at the time), as well as records on several of the Egyptian scholars who contributed to the advancement of Egyptology. Taken together, we believed these and other documents in the archive would shed light on the social history of such actors and reveal how individual Egyptian scholars and heritage workers participated in and shaped the early history of Egyptology, illuminating what roles they played and how these roles changed over time with shifts in politics, ideologies and nationalist identities. But first we had to sort through the papers.

THE GREAT SORTING

The inaugural season of work, from April through June 2017, had a daunting goal – to rescue and assess the most precious of the documents, especially those strewn on the floor, and to begin the painstaking labors of sorting and conservation. Those tasks would soon be followed by the mundane but critical chores of copying, digitizing, transcribing and translating. We also needed to build an online database as well as a safe storage area where the documents would be protected from both pests and the elements.

The slaughterhouse itself provided our working space, so we furnished one of the more protected rooms with two photography stations, a conservation workspace, numerous shelves for sorting and storage and several desks and chairs. The archive itself, deposited in boxes and sacks that were overflowing with jumbled and tattered papers, was moved from the adjacent open-air chamber into the relative safety of our workspace. Only a small number of documents were damaged beyond repair, so we were able to salvage the vast majority of records. With an exact count still to come, we nevertheless determined the documents to number in the tens of thousands. Some of the documents had been bundled with string to contain individual papers, files and ledgers. We did not have time to open every bundle, but it appeared they were grouped for a reason. For example, a bundle might contain the records of a specific antiquities inspector during his or her career. Similarly, files inside the bundles also contained related documents. One example is a file comprising the monthly inspection reports for 1968-69 by Dorothy Eady, the famous Abydos gadfly-expert better known as “Omm Seti.” Another file contained the collected records of famed Egyptian scholar Labib Habachi, one of the first Egyptology graduates from Cairo University (1928), who worked for the Antiquities Department for over 30 years. Many of the documents highlight the extent of the influence Egyptian heritage workers had in the antiquities’ service, even at a time when the institution was still led by the French and dominated by the British. A 1916 letter written by the famous foreman Ali Mohamed Suefi, also known as “Petrie’s best lad,” to Pierre Lacau, shows that Suefi was influential enough to correspond directly, and not through an intermediary, with the then-general director of antiquities. A 1922 official missive from the Egyptian director of Middle Egypt instructs Reginald Engelbach, the British then-chief inspector of Upper Egypt, to cover for his countryman Gerald Wainwright, who held the same position for Middle Egypt. These documents show that Egyptian scholars and excavators, contrary to the prevailing narrative, not only actively engaged with their heritage, but also wielded influence over foreign scholars to a greater extent than previously thought. Additional documents, such as the index file with case numbers assigned to different topics in the archives, shed light on the way the overall work of the inspectorate was organized. This critical file allowed us to connect documents even when their relationship was not obvious. Finally, the ledgers – which could be part of a bundle with other documents or tied up as several ledgers together – recorded every document, request or letter coming to or from a specific inspectorate. These ledgers offered a fascinating overview of the day-to-day bureaucracy of the inspectorate.

The focus of our first season was not the bundles, however, but the loose papers that over time had become dislodged from their bundles and ended up strewn across the floor. This was the part of the archive most in need of conservation. In contrast to the bundled files and papers, these documents were jumbled into a chaos unconnected by topic or date. The entire team joined in this preliminary sorting, organizing the loose paper as best as possible by subject matter. The procedure was basic – piles and stacks on floor and shelves. After two weeks of this sorting, the broad topics and types of documents were revealed enough to design a more systematic process that would guide our work for the next two and a half months.

OLD PAPER, NEW PROCESS

With the adjacent chamber emptied and a rough categorization in place, most of the documents in the archive could be shelved in individual piles in our workspace. Next, priority documents from different batches were retrieved from the piles and taken through the processing system. These documents received special attention because they were the oldest, mentioned a person of significance, and/or referred to an important historical event. These and other papers were to once more face a bureaucratic process, this time a multi-step system for which the ultimate goal is to share the archive with the world.

The first step was to assign a number to every document to enable searching by topic, persons, place, date or other details. We also recorded the physica land thematic context in which the documents were found. This necessitated a hierarchy of numbers, because documents found together in a file could have been written on different dates and mention different sites even though they were related to the same topic.

As any researcher recognizes, this meticulous work is important. Our system relied on obvious tags: C for catalogue numbers, L for ledgers and D for drawings, illustrations, maps and squeezes. Files (F) and bundles (B) also featured unique catalog numbers for individual documents. The loose documents and files from the floor of the storage chamber were assigned to Bundle 0. At the end of the season, over 6,000 catalog numbers had been assigned, in addition to 10 ledger numbers and 26 drawing or map numbers.

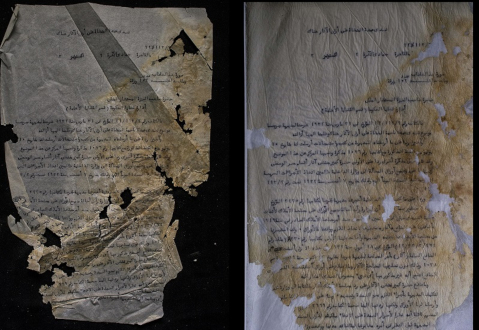

After numbering, each document was photographed. Because many were fragile, this initial stage of documentation was carried out without any attempt to unfold a crumpled document. Meanwhile, our two experienced paper conservators had plenty to do. After the initial photography, the conservators assessed each document, tested its ink and cleaned it mechanically and chemically. The ink was then fixed, and any paper was unfolded or flattened to be mounted and stored acid-free. By season’s end, 443 documents had been conserved, including squeezes, (mirrored copies of the inscriptions) maps, loose papers and ledgers.

In the next step, conserved documents were photographed a second time to record the new state of the document and any new information revealed by restoration. After that came translation, which started with transcribing handwritten documents. Not surprisingly, most documents were in Arabic, and thus translated to English. Documents written in English were instead translated to Arabic, and French and German records were translated to both English and Arabic, to enable researchers to search the database in both languages.

An archive’s safe home is one of its most import- ant features. To protect project documents and preserve them for future generations, conserved documents were placed in acid-free boxes on custom aluminum shelves in our workspace. Documents awaiting conservation were temporarily shelved and covered with protective plastic to prevent contamination by vermin. These documents were also sprayed against silverfish infestation and will be inspected at least monthly until our next season’s work later this year.

AN ARCHIVE IN THE WORLD

Another important step, of course, is the one that eventually will allow researchers not only in Egypt, but worldwide, to view, study and use the Abydos archive. We designed a custom database for easy searches by topics, themes, areas and/or people mentioned in the documents.

Our layout recorded dates, areas/regions, names, titles and institutes in addition to a general description. For the Abydos archive project, we also captured attributes of the document itself – type, color and number of handwriting(s), the paper used, stamp impressions, even whether the document had been reused. Additional database layouts were created for translations, transcriptions and photos, as well as details of the conservation process. Buttons on each layout allow for easy navigation.

This attention to detail took hours of work. To speed data entry, the project computer was set up as a server so we could connect up to five personal computers and iPads at the same time. The result, by the end of our season, was that 541 catalog records, 20 drawing records, six map records, 10 files and two bundle entries had joined the database.

In future seasons, we intend to enhance our system of recording and cataloging, enter thousands more records into the database and create a more suitable and sustainable storage system for this trove of rare documents. Additionally, we are taking steps to collaborate with other archival projects related to the early years of Egyptology and plan for a possible workshop on that topic soon. Amid this work and plans, we continue to reflect on the unique perspective of the Abydos archive to highlight the contributions of indigenous archaeologists in the evolving narrative of Egyptology. It all began with a floor full of scattered paper.